A Visit to Dejima — Japan's Edo Time Capsule

The man-made island in Nagasaki was the only place where foreigners could work and reside in Japan for over 200 years.

Walking down the streets of most major cities in Japan makes it quickly apparent that there are more foreigners visiting and living here than ever before.

While many outsiders have the image of this country being isolated from the rest of the world, Japan had a peak of over 31 million tourists in 2019 right before the pandemic upended all of our lives.

For over two years, Japan closed its borders in one of the strictest responses to COVID-19, and it’s only recently that the government has returned things to normal.

More cynical observers called pandemic-era Japan a return to sakoku, or the “locked country” policy of 265 years where virtually no one could leave or enter Japan on penalty of death.

Needless to say, I always found these claims to be exaggerated and without much merit. While the Japanese government unwisely barred foreign residents from re-entering the country if they left, this unpopular policy was relaxed in the summer and fully reversed by Sept. 2020.

It should also be remembered that the government even briefly tried to ban its own citizens from re-entering Japan if they visited certain African countries designated as high-risk locations for the omicron strain of COVID-19. For me, this ended the implication that the current Japanese government had some kind of xenophobic grudge against foreign residents.

I bring all of this up because toward the end of 2022, I was given a reminder of what a “locked country” policy for Japan really looked like when I visited Dejima island in Nagasaki.

The period from 1641 to 1854 when Japan closed itself off to the rest of the world always fascinated me even long before I moved here or studied the language.

A century of contact with Westerners had seen shogun leaders who were both fascinated and disgusted with what the Portuguese and Dutch had to offer them. While Japan benefited from new technology like high-quality rifles and eventual cultural staples like tempura frying, the shogunate grew weary of the political and religious machinations Rome’s Jesuits had tried to impose.

Thus the decision was made to expel the Portuguese and keep the presence of the Protestant Dutch to a bare minimum in one location where the benefits of trade would be maintained, but the negative influences from foreigners would be isolated.

The Tokugawa shogunate achieved this by building an artificial island in 1636 called Dejima (literally “exit island”) right in the middle of Nagasaki Bay. At a mere 120 meters (390 ft) by 75 meters (246 ft), only a small bridge connected it to the mainland.

If one goes to Nagasaki today, they can visit a “Dejima,” but it isn’t the one the Dutch inhabited centuries ago. Fires in 1798 destroyed most of the original buildings, while the eventual opening of Japan to the West in 1854 made Dejima obsolete.

Time, the elements, and improvement works projects ultimately led to the majority of the fan-shaped island being reclaimed by the surrounding sea. Interest in Dejima was revived in the 1950s, but plans to restore the site did not begin officially until 1996.

Dejima is still undergoing restoration as of 2023 and it seems that this is a project that will take many more years to undertake. But then again, the island has never really stayed the same for too long in any era.

Being there in person truly feels like you’re stepping into an odd time capsule of sorts and you can’t help but imagine what it must have been like for its hundreds of revolving foreign residents who could only stay there and go nowhere else.

As was the case hundreds of years ago, there is but a single bridge connecting Dejima to the mainland of Nagasaki. Like so many other historical sites that can be found throughout Japan, the ancient aesthetics clash with the modern buildings of the urban surroundings.

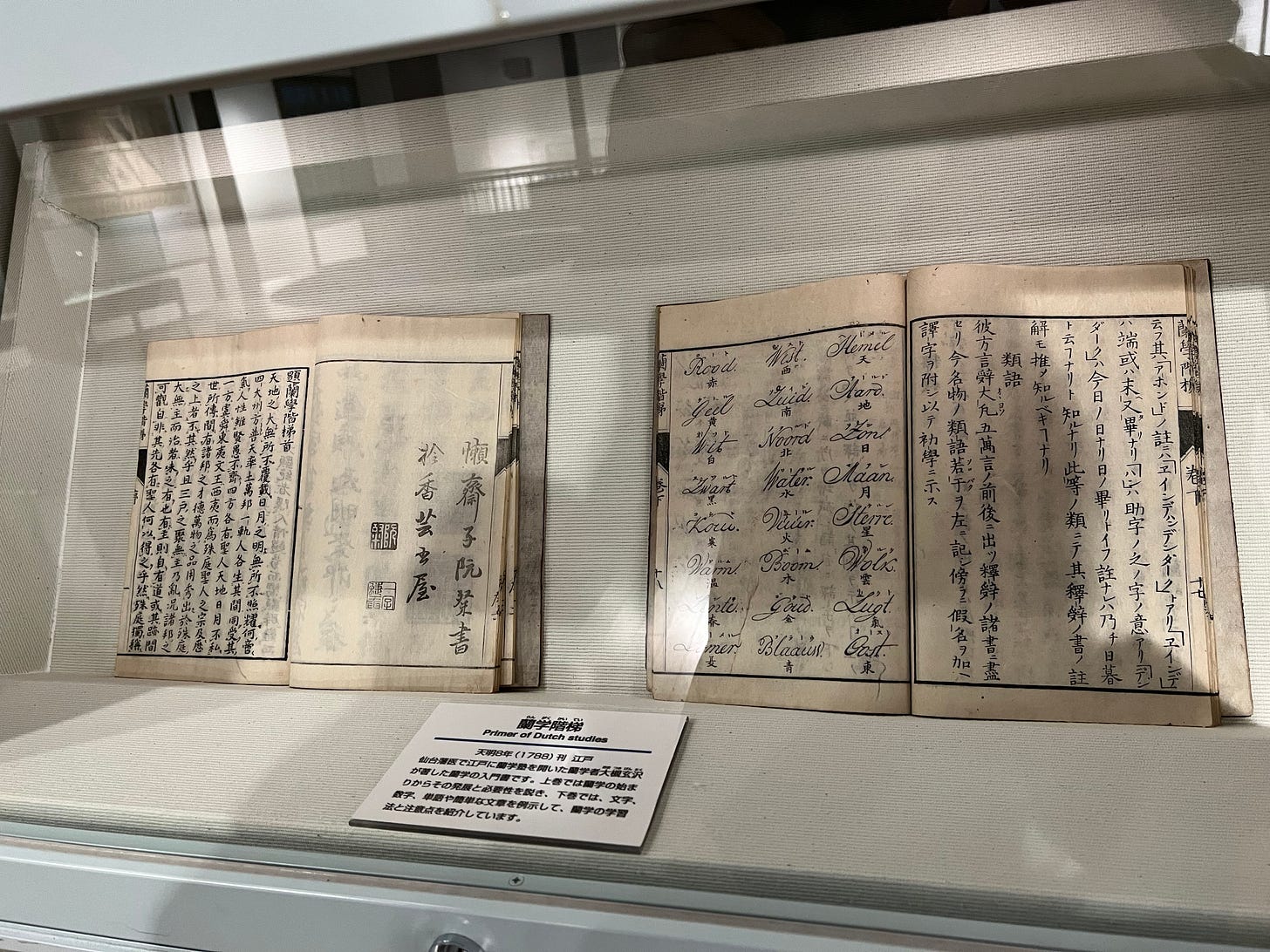

Dejima now is essentially one large interactive museum split across multiple smaller buildings that aim to emulate the architecture and feel of the island in its bygone days. For hardcore history nerds like the present author, it’s a fascinating look into how the Dutch spent their daily lives essentially stuck here with little else to do outside of work hours.

You quickly learn that smoking was a daily part of most people’s routines, while many attempted to recreate as much of European life as possible despite the limited resources.

Beyond tobacco, billiards, cooking, books, and maybe the occasional Japanese consort if one was lucky, I thought to myself that these Dutchmen must have tried hard to avoid loneliness and melancholy so far away from home in a country that was largely hostile to their existence.

But perhaps the most fascinating building is one that aims to reconstruct the living quarters of the VOC Opperhoofd or the trading post chief of Dejima, which rotated out every year. Seeing the European-style wooden furniture, utensils, and glassware paired with the Japanese-style tatami mat flooring and paper sliding doors shows how even back then both cultures were mixing with one another.

Dejima is not just a look back into Japan from hundreds of years ago, but also a reminder of the very different position the Netherlands occupied back then. From the end of the 18th century to the beginning of the 19th century, France’s conquest of the Dutch severely weakened its position on the world stage.

As illustrated by one anecdote on display, the English attempted to take advantage of this by taking over the Netherlands’ possessions, but the Dutch refused to hand over Dejima and proudly flew their national flag — the only place in the world at the time where this was possible.

The rest of Dejima largely consists of other museum exhibits which cover practically every single element of the island you could think of, from discovered ceramic artifacts to even the original soil composition. There was a high-class restaurant that was out of my budget, a Christmas tree display for the season, and even a mini-model recreation of the original location.

Other parts of the island still feel very much work-in-progress, which means that if I were to ever visit again, I imagine I’d have even more to explore.

And therein lies the fascinating draw of Dejima. It’s an island that has never existed naturally, being in a constant state of renovation and expansion to fit with the times. While belonging to the government of Japan, the European culture that was allowed to flourish resulted in a unique place that inhabited both worlds.

Today one can visit Japan via airplane and arrive in less than a day, but it would have taken the average European in the 17th century roughly two years by ship to reach the Land of the Rising Sun. Apart from being the only place where foreigners could stay, Dejima was also the only way they could experience anything close to home for the entire duration of their assignment.

Whatever feelings of loneliness or isolation many of the island’s Dutch residents must have felt back then likely were not too dissimilar to what many foreigners might still experience in Japan today. But Dejima is also a reminder that relations between both Japan and the West have come a very long way, and that there is now far more room for mutual cultural interaction than ever before. Do visit if you’re in Nagasaki.

More photos:

Fascinating article. I really appreciate how meditative of a travel log this was. You not only spoke about what you saw but also what you felt and what the place must've meant to people in the distant past. A great start to your Substack! I hope to see more like this in the future!