AI is Not the Solution to Bad Translations of Japanese Media

A brief history of translation vs. localization and why artificial intelligence won't solve the problem of "woke" localizers.

The publication of the King James Bible in 1611 forever changed the Western world in bringing the Old and New Testaments to a wider English-speaking audience than ever before.

Whether you’re religious or not, chances are high that you’ve used phrases like “at my wit’s end” and “the skin of my teeth,” all of which come from the most famous edition of the Bible. But while it’s the go-to version of the text for many today, religious scholars at the time intensely debated the quality and accuracy of the translation.

If you want to read Wu Cheng’en’s epic Chinese novel Journey to the West, there’s a translation by Anthony C. Yu and another one by William John Francis Jenner, which is personally more nostalgic for me since it’s what I grew up with. On the other side of the world, there are dozens of different translations for the epic Spanish novel Don Quixote and I doubt they will ever stop.

This gives you the idea that people have been arguing over how to interpret works from one language into another ever since humans started putting things down on paper in the Mesopotamian era thousands of years ago. This has not changed today, and a current topic that is dominating translation discourse is the English releases of Japanese media.

Japanese video games, anime, and manga are more popular than ever now worldwide, and passionate fan communities have loyally supported their favorite franchises for years. We’ve come a long way from American television networks like 4Kids TV infamously removing all references to Japanese culture from shows like Pokémon and Kirby: Right Back at Ya!, with fans demanding far higher standards for how these properties get released overseas.

Yet in the last few years, some translations of Japanese properties into English are coming under fire for everything from censorship to the unsubtle insertion of political statements that were nowhere to be found in the original native script. Like many things in the West these days, much of this has become fodder for culture wars that often devolve into unproductive online mudslinging thanks to a minority of translators and localizers who think it’s their business to do things like this.

The announcement that the manga series The Ancient Magus’ Bride would be relying on AI technology to translate the original Japanese text to English only poured more gasoline onto the fire. The replies to this tweet have many claiming that the era of “woke” localizers is over, while yours truly was caught in the crossfire after I weighed in with my own thoughts. Namely, that I don’t think artificial intelligence will pan out as a viable solution to existing problems around localization of Japanese media.

The result of this was many days of angry people in my mentions claiming that I had sold out and taken the side of the woke, despite other posts of mine explicitly criticizing such people and their views. Alas, that is the nature of social media where nuance goes to die, but I doubt readers of this Substack care about such petty drama. Regardless, I do think this is a subject which deserves a full write-up, hence why you are reading this article now.

This piece took far longer to write than I initially planned, but its length reflects how translation really is a complicated topic that requires a lot of nuance when discussing. I still feel that I’ve only scratched the surface, but there are few points that I wanted to make sure were included in this piece. As someone who has studied Japanese for over a decade and lives in Japan full time, translation is something that I’m well acquainted with even if it isn’t my profession.

Additionally, I have grown increasingly troubled by this gung-ho embrace of AI when we are just beginning to understand the implications of the technology. I personally believe that artificial intelligence is largely a creative dead end when it comes to artistic fields such as translation, and it won’t bring the results that some seem to think it will in combating poor localizations. Those who do not speak Japanese underestimate just how difficult it is to translate the language into English, while those who translate as their job shouldn’t be making excuses for poor work.

Translation vs. Localization

It’s first important to properly define the difference between “translation” and “localization.” While the two terms are often used interchangeably, they actually do mean different things and carry important distinctions.

Translation in a basic sense is the direct conversion of one language into another. If you want to get even more specific, “translation” is rewriting one language into another, while “interpretation” is for spoken language. Many tend to call interpreters translators, though they are technically separate roles.

Localization is the offspring of translation and requires significant consideration of the culture and intended audience of the target language. For example, the Japanese phrase itadakimasu (いただきます) which is said before meals means “I humbly receive” if literally translated into English. Most translations, however, would render this phrase as something like “Bon appétit!” or “Let’s eat!” as those are more natural and carry essentially the same meaning.

That’s a very simple example of basic localization of Japanese to English, but it can get significantly more complicated. If a video game script has a character speaking in Japanese haiku, should the translated English text aim to get the original meaning or preserve the original 5-7-5 syllable structure? A good localization would attempt to do both, but this is where considerable creativity and imagination are necessary. It’s also important to note that translation and localization are sometimes handled by the same person, and sometimes they are not.

Japanese animation, or anime, began to infiltrate the United States in the 1960s, but in heavily modified form. If you’re in your 20s like me, anime such as Astro Boy, Speed Racer, and Kimba: The White Lion are probably what your parents grew up watching, but many were none the wiser that these shows were from Japan because of how much their English dubbing catered to American tastes. These are clear examples of localization. It wouldn’t be until the 1990s when more translations of anime began focusing on keeping the “Japanese-ness” intact, since by that point there was more interest in Asian culture among Westerners.

The same held true for other media like manga (Japanese comics) and video games. When Nintendo hit the scene in the 1980s with their NES console, many Japanese games were heavily censored or modified for their overseas release. This topic alone is enough for its own article, but I highly recommend checking the website Legends of Localization for a fascinating breakdown of this process. These practices are why the original Dragon Quest ended up having a famous (or infamous depending on who you ask) pseudo-Elizabethan English localization, and the invented localized line “You spoony bard!" from Final Fantasy IV is the stuff of early internet meme legends alongside “All your base are belong to us.”

As is to be expected, there are things between Japanese and English that do not smoothly translate between one another. Some translations aim to be as literal as possible, but often end up stiff and dry. Others take on a more liberal interpretation of the original text which improves readability, but the risk is higher of important meanings or nuances being lost. Localization attempts to bridge this gap between languages by creating a cultural equivalent that conveys a similar meaning, but as we will soon see, this can result in creative decisions that range from clever to awful.

Localization: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

Localization has become a highly contentious topic in recent years, with many hardcore fans of Japanese media decrying the practice as censorship, cultural erasure, and/or dumbing down foreign content for Western audiences. And sometimes, that’s certainly true.

While some localizations began adhering more to the original Japanese source material from the 1990s onward, many rights holders in foreign countries were adamant that things had to be changed. What is considered appropriate for children’s media in Japan is often much looser than in the United States, which is why the network 4Kids TV notoriously watered down shows like Pokémon and One Piece for their American broadcasts in the early 2000s. While some of these changes were aimed at reducing violence or bloodshed, other bizarre alterations resulted in things like onigiri rice balls being changed to jelly donuts, despite the animation clearly showing the former.

The United States is famous for its moral panics toward seemingly everything from Dungeons and Dragons to Harry Potter, so in some sense one can sympathize with a television executive having the thankless task of selling foreign media to millions of households that probably have more than a few couch-fainting moral busybody parents. Children’s television programming standards in the U.S. are particularly strict, meaning that rights holders like 4Kids had little choice but to engage in censorship. We seem to have mostly moved on from this era when it comes to overly zealous localizations in this manner, but context is necessary in understanding why these changes occurred in the first place.

Indeed, sometimes localization is unavoidable. A notable example with this is Capcom’s Ace Attorney series of adventure games. Originally released in 2001 for the Game Boy Advance as Gyakuten Saiban or “Turnabout Trial,” it did not hit stateside until 2005 when the series began getting ports for the Nintendo DS. This franchise can essentially be summarized as a visual novel courtroom drama, but the landscape for such text-heavy games was very different outside of Japan nearly 20 years ago. For the uninitiated, a visual novel relies mostly or entirely on text and contains little to no gameplay in the traditional sense of video games, with story being the main focus.

Previous visual novels such as Snatcher and Ever 17: The Out of Infinity were commercial failures in the United States, which made Capcom cautious of releasing Gyakuten Saiban overseas. But considering that the DS attracted a wider audience of gamers of all ages, it decided to take a chance with the first game. Thus, Gyakuten Saiban was rechristened as Phoenix Wright: Ace Attorney with the Japanese setting and names heavily modified for Western audiences. Translator Alexander O. Smith faced issues with adapting Japanese puns and wordplay, so English alternatives were provided instead of literal translations.

While it is easy to take issue with the heavy changes Gyakuten Saiban underwent today in retrospect, such measures were necessary to market what was otherwise a very niche game to Western players in 2005. But the game proved to be a sleeper hit, which resulted in the rest of the series being localized, and in turn the beginning of visual novels finding an audience outside of Japan. Ace Attorney protagonist Phoenix Wright is now one of the most popular video game characters, yet he arguably would not have gotten there without localization that was aimed at a wide audience. On the other hand, the shift in game setting from Japan to California created storyline issues with later titles in the series, something that is the subject of many jokes among the fanbase.

Similar visual novels like Zero Escape and Danganronpa would later be released with more faithful translations, but by then acceptance of distinctly Japanese media had become widespread. Indeed, that is now largely the appeal of Japanese video games and anime. Western audiences are increasingly desiring media that provide them with cultural experiences that are distinct from their own, which is why series like Persona and Yakuza (now called Like a Dragon to reflect the original Japanese name) are very popular. If Gyakuten Saiban were released today, it likely would have kept the Japanese setting and have less reason for drastic changes.

This brings us to current debates around “how much” localization is needed, and that question is largely going to come down to what media is being discussed. Pokémon is going to have a far different kind of localization than Persona because the former is aimed at kids, while the later is aimed at adults. Some countries have strict regulations regarding what content is allowed in media, which means that changes are necessary by law. Many are often unaware that Japanese localizations of Western games are often heavily censored, meaning that this is hardly just a one-way issue.

Recent criticisms of English localizations, however, stem from accusations that the people in charge of them are inserting political statements often related to U.S. culture wars which are a stark departure from the original Japanese scripts. If we look at some of the most egregious examples of this practice over the last few years, the evidence does appear to be damning.

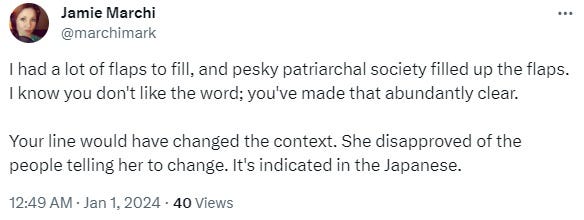

The above photo with the anime Miss Kobayashi’s Dragon Maid is often cited in these discussions as a notable example of “woke” localization. While these kinds of shows are not my cup of tea and I’ve never listened to the Japanese audio, it’s pretty obvious to even monolingual viewers that “pesky patriarchal societal demands” is not something the original author wrote. At best, we can call it a very liberal interpretation of the translated line in the subtitled version, but I think most would call it a bad creative choice.

Well, the localizer Jamie Marchi doesn’t seem to think so. During a 2018 convention appearance, she blamed fans’ dislike of the line on misogyny and bluntly told her critics, “I have a vagina. Deal with it.” She has since continued to double down on Twitter as seen below with some points that are worth noting.

It should be noted that Marchi is NOT a translator and her comments on the Japanese language carry little weight. Her job at Funimation is to adapt a script which has already been translated into English from Japanese and rewrite it for dubbing, which in fairness does require some changes. This holds true no matter what language a show is being dubbed into. But as an outside observer, I find most of Marchi’s points to be rather weak defenses of what’s a pretty terrible interpretation of the original script.

Another example of “woke” localization that also gets commonly cited is the English script for the video game Ghostwire: Tokyo in which the line “All property is theft” appears despite no such socialist message being in the Japanese script. Having listened to the spoken Japanese dialogue (さあ、どうだろうな, lit. “Huh, I wonder.”), I have no idea how whoever was behind the localization came to that interpretation. The Chinese translation appears to be based off the English line because it too is inaccurate.

The backlash was so severe from fans that the offending line was actually removed in a later patch, which suggests that even the publisher Bethesda probably realized that they had screwed up, which raises the question around what other problems Ghostwire’s English localization may have.

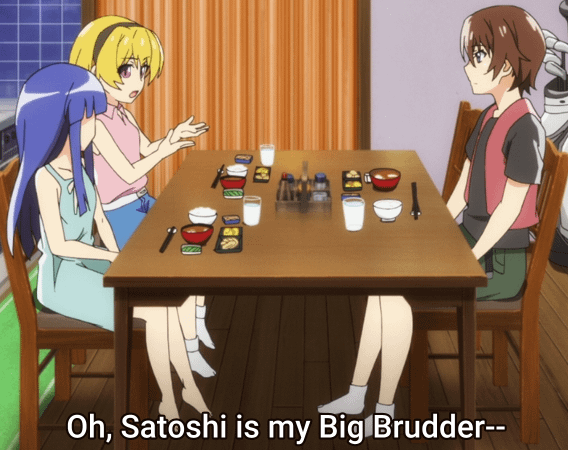

In another controversy, translator Katrina Leonoudakis (who in this case is also responsible for subtitle localization choices) rendered the phrase “Nii-Nii” in the anime Higurashi When They Cry: Gou as “Big Brudder.”

To provide some context, “Nii-Nii” is essentially a childish nickname a small child would give to an older brother. In Japanese, children often refer to their siblings with forms of address like “big brother” or “little sister,” which can pose a challenge for translators. Does one literally translate “onii-chan” as “big brother” or leave it be? Leonoudakis’ translation of “Nii-Nii” as “Big Brudder” is in my opinion a rather unnatural-sounding middle ground between both, and fans of Higurashi certainly took note.

Translators from a different school of thought will often keep names like “onii-chan” and honorifics like -san or -sama intact both for subtitling and dubbing to preserve the intricate Japanese system of social roles, while others believe none of it should be included in an English script. The problem here is that Higurashi fans have long associated the character Satoko with saying “Nii-Nii” in previous translations of the franchise’s games, anime, and manga. Yet when asked about it, Leonoudakis defended her writing choice and is known for being dismissive of critical fans just like Jamie Marchi.

In the end, however, the fans won out. Ironically, the dub of the show still has Sadako saying “Nii-Nii” and the following season would remove “Big Brudder” from the subtitles entirely. Like Ghostwire: Tokyo, I can only speculate that this happened because of fan backlash. Leonoudakis is now rather infamous among anime watchers for her translations, and her behavior on social media has only contributed to the recent stereotype that all translators/localizers are woke social justice warriors. Yours truly is also blocked by her despite never having a single interaction.

These above examples and more are pretty clear examples to me of bad localizations, but I must emphasize that they ultimately represent the minority of English translations of Japanese media. I can personally vouch for translators like Jeremy Blaustein (Snatcher, Metal Gear Solid) and Jake Jung (Made in Abyss, Future Boy Conan), who are friends of mine and do excellent work which has been widely lauded by critics and fans alike.

Privately, some translators have expressed their dislike of the above localization examples to me and take issue with their colleagues being so hostile toward fans. To blindly generalize all translators and localizers as bad people with a political agenda is unfair and not reflective of the majority who are respectful toward the Japanese source material. The problem is that the worst examples of localization stick out and are not easily forgotten by passionate audiences who have the right to demand better quality of work overall.

Is Artificial Intelligence the Future?

The controversy over poor localizations has only been ignited even further with The Ancient Magus Bride, a manga that will now receive a simultaneous English release via artificial intelligence. The official Twitter account for the series stated that their system “combines unique machine translation technology with editing and proofreading by professional translators.” The replies showed a mixture of responses ranging from praise to criticism, while the subreddit appears to be generally displeased with the decision. But how does the translation actually read? Here are some comparisons.

While this is ultimately subjective, I still feel that the translation done by a human being feels more natural and reads smoother than the AI version, which comes across as rather stiff and (unsurprisingly) robotic. But even the AI translation is being proofread by a human editor, which means that there is still the possibility of changes being implemented. Some seem to be under the impression that Japanese publishers are becoming aware of woke localizers heavily changing their products, but I don’t think that’s the case here.

The simple reason for this use of AI is that the manga’s publishers are trying to cut corners to release a quick English version without having to pay for translators. Whether true or not, the previously-linked Twitter post cited damages from piracy as the main justification for turning to AI. While this may become a practice for more niche series, it’s highly unlikely that a company like Nintendo or Atlus will use AI anytime soon due to their greater budgets and overall quality standards.

To give credit where it’s due, machine translation from Japanese to English has made leaps and bounds from the days of early 2000s Google Translate and Yahoo Babel Fish. New technology like DeepL can provide some impressive results when it comes to straightforward texts like news articles or medical journals which require little creative interpretation. When it comes to works of fiction like manga or video games, however, the results are more mixed.

Combining AI translation service ZTranslate with the retro video game emulator application RetroArch allows users to play Japanese games in English, but I’m frankly not very satisfied with the final output as it currently is. ZTranslate relies on optical character recognition (OCR) technology to convert images into translatable text, but it’s notoriously finicky with Japanese. For example, I’ve taken Japanese subtitle files from DVDs and Blu-rays in an attempt to apply them to higher quality video sources taken from 4K UHD rips, but available OCR applications do a poor job in reading the Japanese text from the PGS files, which contain hiragana, katakana, and kanji as image files.

Of course, I’m sure this technology will eventually get better and something like ZTranslate is presumably using an upgraded version, but we still have the problem of the resulting translations feeling unnatural or lacking things such as character speech patterns, gendered pronouns, and regional dialects that were inherent to the original Japanese text. English-speaking fans of visual novels have used machine and AI translations for certain niche titles for quite some time already, though a look at online forums will illustrate that there are still numerous problems to overcome.

These AI translations are serviceable for online communities who simply want the basic gist of a story in English, but a professional company like Nintendo, which is selling its products to millions of consumers worldwide, is going to have far higher standards and would never resort to a machine translation. If AI translation reaches the point where most of these imperfections are ironed out, bigger companies may adopt them as a partial tool, but there will always be a human being at the end of the line to make sure nothing goes out the door before a final check.

Nintendo’s division Treehouse doesn’t just translate its games either; it also makes sure that they’re being localized with the culture of the target region in mind. The Fire Emblem series is particularly notorious for having content cut or censored for its overseas releases, but this isn’t just because of some overzealous woke localizer. Rather, it’s official company policy for Nintendo to make these changes, and those practices will remain the same regardless if AI translation is being used or not.

I understand the frustration many English fans of Japanese media have toward these alterations, and I myself have a strong dislike of any form of censorship, especially when it comes to media that is aimed at mature adult audiences. I have previously written of my opposition toward this patronizing hand-holding many media companies are practicing these days, but I don’t think AI translation is going to make these problems go away.

What Can Be Done

When a localization is bad, what are fans to do? While it may seem that consumers have little power over these changes, this does not necessarily have to be the case, especially now when the internet and social media allows more transparency around development than ever. There are no perfect solutions, but there are a few things that I think can push things in a better direction.

As I mentioned previously, the bad localization choices seen in games like Ghostwire: Tokyo were eventually removed altogether. This suggests that the negative response was loud enough to not go unnoticed by Bethesda, resulting in a later patch changing the text. This to me is the most direct way for fans to express their displeasure around poor localizations of video games. If enough people are loud enough, companies are likely to be more willing to listen and act accordingly.

The same also holds true for manga and anime. Like Ghostwire, fan dislike over the translation of one season of Higurashi: When They Cry seemed to lead to changes in the following season. Moves like these will happen if it’s clear that a sizable amount of consumers are dissatisfied with a certain product. The downside is that this may not be possible in every situation and some companies like Nintendo will likely be more stubborn.

Another solution, which I think is the best course, is for fans to take matters in their own hands when official releases fall short or don’t even exist at all. Fan translations of video games, anime, and manga have been around for decades at this point, and yours truly even played a small part in bringing Hideo Kojima’s Policenauts to the Sega Saturn in English as a playtester back in 2016. The release has been positively received with many comparing it to an official localization, and I can guarantee you that such work would have not been possible through the use of AI. The same can be said about translation patches for other Japan-only games like Mother 3 and Shin Megami Tensei if..., which have also been strongly praised for their quality.

Of course, fan translations have their drawbacks. While PC modding is usually relatively straightforward, changing console video games requires hacked hardware, which can be a hurdle for some. Many projects get started, but don’t see the finish line. Some companies threaten legal action against fan groups, which leads to them shutting down for good. And of course, one has to keep in mind that fan translators, like official paid translators, may have interpretations of Japanese text that differ from other fans.

As English writer George Borrow once put it, “Translation is at best an echo.” All translation is someone’s individual interpretation, which leads to another possible solution, though it’s obviously the most difficult one: learn Japanese from scratch. Whether it’s a human being translating something from Japanese or AI software utilizing deep learning, the resulting text is always going to be one “opinion” over how something should read in another language. This gets into a deep philosophical debate that’s beyond the scope of this article, but I can attest that being truly bilingual opens doors in a way one never would experience if they were only monolingual.

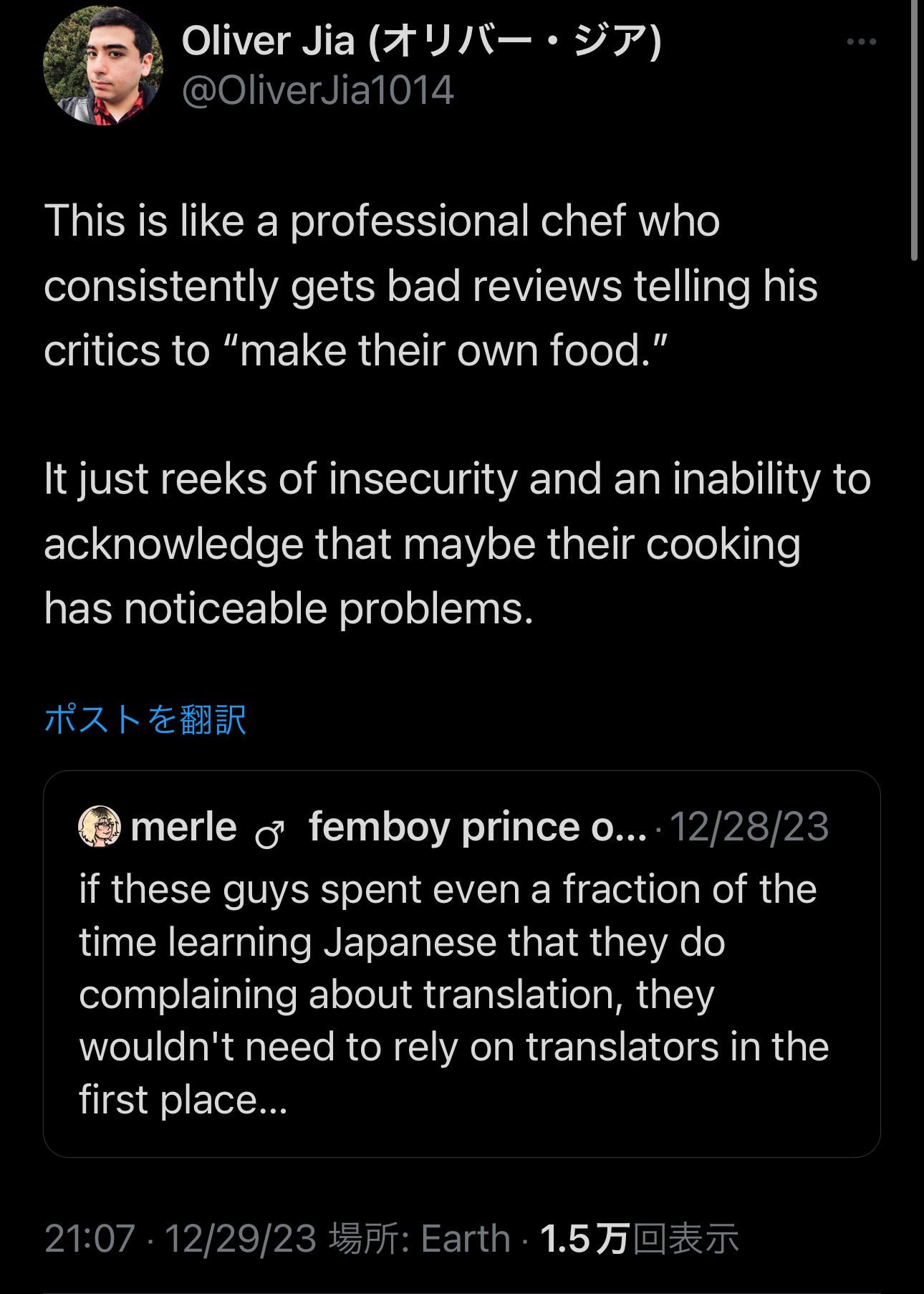

In the future I plan to write a piece outlining how I learned Japanese over the past decade, but in my many years of studying the language, I’ve used text-heavy games like RPGs and visual novels as a supplementary learning tool. While I don’t think one can become fluent in spoken Japanese without spending an extended amount of time in the country at some point, one can actually get to a decently high level in reading Japanese without ever stepping foot in Japan. It’s a long process and those who are not committed to daily studying shouldn’t even start, but the rewards are worth it. With that in mind, someone whose job it is to professionally translate shouldn’t be suggesting that one learn Japanese as a retort to criticism of their work.

It is all too understandable why fans of certain series would be hostile toward localizers who display the above attitude. Without resorting to harassment, I believe that these people should be called out for their laziness and agenda-pushing when appropriate. Musicians who perform poorly don’t tell fans to “play their own music,” nor should a translator or localizer tell fans to “learn Japanese” if they’re bad at their job. I will admit that it does feel satisfying knowing that I no longer have to rely on someone else’s translation when I know Japanese myself, but that shouldn’t be a prerequisite when most want to enjoy media in their own native language.

Don’t Throw the Translator Out with the Bath Water

As someone who has been studying Japanese for nearly half of his life, linguistic differences and how to bridge them have always interested me. One inspiration for learning the language was indeed media like Japanese films and video games, but never did I think that translation would be yet another talking point in these tiresome American culture wars.

I’m no fan of the woke localizers and the backlash against them is warranted, but at the same time, these controversies have lead to some people saying some very silly things. My friend Jeremy Blaustein is the man responsible for the localizations of games like Snatcher and the first Metal Gear Solid, work that has generally been well-regarded by fans for years. Yet upon my praise of his contributions, I was met with some unnecessarily rude comments that took me off guard.

This doesn’t even include some of the more vile and antisemitic stuff sent Jeremy’s way which I don’t feel like reposting here. But apart from these kinds of replies being completely uncalled for, they’re also engaging in odd revisionist history. I distinctly remember Metal Gear fans constantly praising Jeremy’s translation even with the liberties that he took. I know this, because upon the release of MGS1’s GameCube remake, The Twin Snakes, fans criticized the new English script (which Jeremy did not write) as being inferior to the PlayStation original. While The Twin Snakes had a more literal translation, the majority of fan memories around the game come from Jeremy’s localization and dialogue choices, as well as him writing terms like “codec” for the wireless radio and “OSP (on-site procurement)” which were not in the Japanese original, but are now staples of the series.

If MGS1 were localized today, there likely would be less changes, but remember that Jeremy handled all of the game’s English script from translation to editing completely on his own over just six months. With casting director Kris Zimmerman, he even played a significant role in how the English dub voice actors should perform his script. Game localization resources in 1998 were a fraction of what they were today and most English voice acting was terrible. The original Metal Gear Solid was one of the first games to work past those limitations and strive for something closer to Hollywood films, resulting in a final product that remains a classic to this day. I highly recommend reading his own thoughts around working on the ambitious project. As he puts it, “translation is not a science; it is an art.”

Another odd take that I’ve recently been seeing is the proposal that Japanese studios will dub their own media with AI instead of relying on English voice actors. Again, I don’t see this as something that will be done other than by low-budget companies trying to save money. Studio Ghibli for example takes a hands-on role with how their films are translated overseas and would certainly not settle for anything less than actual voice actors. Some fans have tried their hand at showing AI dubbing in action and while it sounds ok, there’s still a feeling of unnaturalness that takes me out of the experience.

AI voice acting is certainly advancing in quality and I have no doubt that it will be used in the future for things like audio cleanup and ADR, but I don’t want to live in a media landscape where literally every aspect from the script to the voice acting of a film or show is created by machines. If you think that Hollywood movies and mainstream popular media are terrible now, imagine what things would be like where there is literally no human creativity involved at all. Publishers and studio executives will cut every corner possible to save money, which is why such practices need to be spoken out against now.

AI is not the solution to bad localizations because an artificial intelligence module is at the end of the day highly dependent on those who’ve programmed it and what results they wish to see. And if you think that arguments over translation and localization are just a Western thing, there is a long history of video games with bad translations into Japanese and criticism of some of the biggest names in the Japanese subtitling industry like Natsuko Toda. Fans on both sides of the Pacific are unsurprisingly very passionate and they can spot a bad translation a mile away.

And to repeat myself yet again, there is always going to be a human editor that will make the final decisions and change the outputted script if they view it as necessary. Localizations don’t happen in a vacuum, rather they’re done with a specific audience in mind. The schadenfreude of seeing woke localizers unhappy is understandable, but consumers shouldn’t be cutting their noses off to spite their faces. Instead of pushing for AI which will degrade the overall quality of media, we should instead be praising those who do a genuinely good job of localizing Japanese media and pushing for them to continue their work. As Miguel Sanz once said, “If the translator does his job as he should, he is a benefactor of humanity; otherwise he is a veritable public enemy.”

Foreign Perspectives is a reader-supported Substack. If you like my work and have come this far as a new reader or free subscriber, consider opting for a paid subscription so I can continue writing in-depth articles such as these on a regular basis. Your support is greatly appreciated!

![Higurashi no Naku Koro ni Gou [Rewatcher thread] - Episode 10 discussion : r/anime Higurashi no Naku Koro ni Gou [Rewatcher thread] - Episode 10 discussion : r/anime](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Y0kZ!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Ffcfa07e3-2e8f-457e-a36b-4f54a7c0acf4_598x373.png)

Really enjoyed this one. I completely agree folks who are outraged over bad localization tend to lump both Translators and Localizers together without knowing what the difference is. (Or that there even is one.)

Is the Marc Laidlaw that was worked on the Policenauts translation you mentioned THE Marc Laidlaw who wrote the original Half Life games, or?

This is a great take. I see why the Twitter crowd wants AI translations, but yes, they will be of worse quality overall. And I do think you’re right that negative examples of localization will stick out so much that all localizers will be painted with the same brush.