Bonus Perspectives: Mr. Trump Goes to McDonald's, A Brief Guide to Japanese Politics, Terry Gilliam's "Brazil," and Brahms' Hungarian Dances

Trump serves up fries as the election approaches, Japan's political opposition gets a boost, and your weekly media recommendations.

Bonus Perspectives is a weekly column series containing my thoughts on the latest international news and Japanese news, as well as film, television, music, book, and video game recommendations. It’s free for all subscribers to this Substack, but if you enjoy my writing, consider opting for a paid subscription. Doing so will give you access to exclusive in-depth pieces and my entire backlog of work. Your support is greatly appreciated!

Paid subscriptions are currently 20% off from now until the end of October.

Trump working at McDonald’s is harmless campaigning

We’re less than two weeks away from the U.S. presidential elections if you can believe it. After a summer of attempted assassinations, the incumbent president announcing that he would not seek a second term, Kamala Harris scrambling to take over, and disastrous debates, this extended soap opera is reaching the season finale. Like most seasons of television though, you need a lighthearted episode before everything explodes at the end. As luck would have it, that’s exactly what happened on Sunday when Donald Trump stopped by a Pennsylvania McDonald’s to temporarily work at the fry station and serve food at the drive-thru window.

The event was obviously organized in advance by Trump’s campaign team, but that’s perfectly in line with similar stunts other candidates have pulled in the past. Hillary Clinton was infamously the subject of an awkward photo in 2016 when she visited public housing in East Harlem, while Mitt Romney’s running mate Paul Ryan embarrassed himself in 2012 when he started washing a clean pan at an Ohio food bank. But unlike those episodes, Trump actually pulled off the act reasonably well and managed to come across like a real human being.

The restaurant was closed to the public and arriving customers were informed that Trump was there. Make no mistake, this was a pre-determined stunt and one of the biggest motivations seems to have been a jab at Kamala Harris who previously claimed that she briefly worked at McDonald’s while a student at Howard University in the 1980s. As far as can be determined, there are no surviving employment records to verify this, but it would also be unlikely that a McDonald’s would have kept such documents for over 40 years. At the same time, Kamala Harris is no different from most other politicians who lie and embellish their upbringing, which can be seen in her sappy memoir full of stories that clearly never happened.

In any case, the McDonald’s stunt is fascinating for how good it actually makes Trump look. I’ve discussed this before in previous columns, but when Trump isn’t constantly bullshitting and getting into crass political mudslinging, he’s fully capable of being a likable person and making others feel valued. He looked and sounded like he was giving the employee training him his full attention, while that young man deserves top marks for his professionalism throughout the whole event. Even me as someone highly critical of the former president can’t help but find Trump’s enthusiastic comments about how the French fries “never touch the human hand” somewhat endearing.

McDonald’s issued what was a surprisingly well-written non-partisan statement affirming that their company does not endorse political candidates, but opens their doors to all. And you know what? I don’t think there’s anything wrong with what Trump did here. It’s doubtful that it will swing the election either way one iota, but it’s classic campaigning that American politicians have done for decades. For Trump, all of this probably came to him naturally since it echos similar down-to-earth moments like working at his own hotel during his television celebrity days.

There were of course people who were less than amused with the stunt, with a Harris campaign adviser slamming Trump as “desperate.” Again though, there’s little reason to believe that this is going to greatly affect the election. The vast majority of Americans decided who they were going to vote for years ago, French fries and Big Macs be damned. I’m just here for the glorious memes and a final opportunity to laugh at the whole situation before the depressing realization sets in that one of these people is actually going to be president come January.

A brief guide to Japan’s political parties

It’s not just election season in the U.S., but also here in Japan too. The general election is set for Oct. 27, which shortly follows the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) electing maverick Shigeru Ishiba last month as their leader and effective prime minister of Japan. While Japanese politics is generally quite dry, especially when compared to the sideshow that is U.S. politics, this is actually one of the most important elections the country has faced in years.

Ishiba is already facing low approval ratings right out of the gate, which comes as the LDP is embroiled in a slush fund scandal that is weakening public confidence. Political scandals happen in Japan as they do anywhere else, but misuse of taxpayer money for illicit means is one of the biggest transgressions an elected official can pull. Ishiba’s predecessor Fumio Kishida resigning can be directly linked to his perceived inability to crack down on corruption, even if prosecutors cleared him and other lawmakers of any connection to the party’s scandals.

Enter Shigeru Ishiba, whose idealistic policies I previously wrote about earlier this month. This is the quickest the Japanese government has held a general election after a prime minister’s inauguration since the end of World War II, which Ishiba is doing to address the skepticism around his administration. All 465 seats in Japan’s House of Representatives are now up for vote by the citizenry, but the opposition parties are taking full advantage in the lack of public confidence toward the ruling establishment with the general elections.

With the exception of Kishida, the position of prime minister has largely been a revolving door before and since Shinzo Abe. Ishiba may end up being one of the many men whose time in office is cut short if the coalition government lead by the LDP and Komeito fails to win a majority during this month’s elections. Given the scandals plaguing the LDP and the fact that it could be facing a potential ideological split with a small, but vocal minority of internal critics like Sanae Takaichi, Ishiba currently has the deck stacked against him.

Truth be told, domestic Japanese politics is something I only follow casually as my field is primarily international relations and foreign policy. As I’ve mentioned before, I recommend the writings of my colleagues Tobias Harris and Gearoid Reidy if you want deeper insights as covering this is what they do for a living. Still, I will use this space to briefly describe each Japanese political party in the election and what their current chances are for victory. Out of the 465 seats, 233 seats are needed for a majority.

Liberal Democratic Party: The ruling party of Japan. A big-tent party, it runs the spectrum of center-right to ultraconservative factions, though it should be noted that these are often loaded terms in relation to what those in some Anglosphere countries consider “right-wing.” It’s been consistently in power since 1955 except from 1993 to 1994 and 2009 to 2012. Despite historically being bitter rivals with the now defunct Japan Socialist Party, both entered a coalition in 1994 as a pragmatic move against the opposition. While Prime Minister Tomiichi Murayama (who is still with us at age 100) was from the JSP, the LDP still had a significant influence on policy at the time which ultimately lead to it regaining power. The JSP soon fell apart due to lack of political support.

The now defunct Democratic Party of Japan ruled from 2009 to 2012, but it failed to gain public confidence as a viable alternative to the LDP. Shinzo Abe took advantage of this political environment and succeeded in getting a three additional terms from 2012 to 2020, making him the longest serving prime minister in Japanese history. The DPJ no longer exists and has a convoluted history of splitting into smaller opposition parties, many of which are also now defunct.

The weakness of the opposition is why the LDP has been able to stay consistently in power until now, but what party leader it chooses can vary wildly depending on the political faction. Abe’s conservative faction has been purged by the more liberal Kishida administration, though a few loud voices like Sanae Takaichi are trying to keep his legacy alive since Ishiba is diametrically opposed to Abe’s ideology. Still, some believe that reality will likely force him to be closer to the more pragmatic leader Abe, and his proposals like an Asian version of NATO don’t seem likely to happen in the near future.

The LDP currently holds 247 seats in the House of Representatives, giving it the majority. The biggest question of this election is how many seats it will lose and if that will be enough for it to become the minority government for only the third time in post-war Japanese history. Some are predicting massive losses for the LDP and some believe they will do better than expected given that most Japanese voters have historically disliked the opposition parties, while others take the more middle view that the LDP will keep its majority but still lose a considerable number of seats due to its scandals.

Regardless of what happens, one thing is for sure — the days of the LDP being able to confidently rest on its laurels are over and the party can no longer expect easy wins.

Komeito: A wacky centrist party that has close ties with Soka Gakkai, one of the largest Buddhist religious movements in Japan. Unlike in America where most expect politicians to make statements invoking God and Christianity, the Japanese public is generally very skeptical of any relationship between politics and religion. Most people you talk to on the street are unlikely to say many nice things about Komeito for this reason, but Soka Gakkai having between 2 and 4 million followers in Japan is why they’ve been able to get a decent number of politicians elected.

The modern day Komeito is a completely different beast from its founding in 1964, having gone from a rival of the LDP to its coalition partner. Domestically, it’s largely promoted social welfare, reduced consumption tax rates, and greater child allowances. On foreign policy, it has evolved from being pacifist to more in-line with the LDP’s support for revising Article 9 of the constitution which would give the country offensive military forces. Do they matter? On their own, not really. But as a coalition member, they’re an important backup which could make or break the LDP keeping its majority. Komeito currently holds 32 seats.

Constitutional Democratic Party: A center-left party that represents the largest opposition to the LDP. The CDP opposes revising the Japanese constitution and is also against nuclear power. While they support the U.S. military alliance, pacifism remains their ideological baseline and they believe in strictly defensive forces only. Their platform is stated to be in favor of same-sex marriage, abortion rights, gender equality, and other typical progressive stances. On the surface, they’re to the LDP what the Democrats are to the Republicans in America, but it’s more complicated than that.

With the LDP being such a big tent party, there are many individual members who have taken progressive stances that win elections amid local constituents. Shinzo Abe famously had his “womenomics” which encouraged women to play a larger role in the workforce, abortion is already de facto legal in Japan with little opposition from the LDP, and same-sex marriage has gained marginally more support compared to the past. With the LDP generally proving to be more competent leaders who will eventually adopt similar progressive views on certain issues anyways, most voters simply go with them.

The CDP currently holds 98 seats and needs 135 to win a majority. This is still a long shot, but the party is taking advantage of dissatisfaction with the LDP over the slush fund scandal and is polling better than it ever has in the past. Personally, I doubt they’ll become the new majority government, but they still could win big in key areas.

Nippon Ishin no Kai: Also known as the Japan Innovation Party, this is another weird political party that would make little sense in an American context given its wide-ranging stances. They’ve often been described as the closest thing to a viable libertarian party in Japan due to their positive views on deregulation and limited government, but they also support things like universal basic income and free education which sound far closer to Bernie Sanders or Andrew Yang than it would to something Ron Paul would push for. Not to mention that their push for removing defense spending limits would probably give most American libertarians a heart attack. They’re definitely a populist party, but quite distinct from the loud minority of far-right ultranationalists many tend to associate with Japanese populism.

Nippon Ishin no Kai was founded in 2015 and currently holds 42 seats, which is moderately impressive for such a new party. They’re primarily against LDP control over Japanese politics, but some of their differences often come across as splitting hairs. There’s no chance they’re ever going to be the majority government barring some cataclysmic change to the entire Japanese political system, but they’re still a party to pay attention to on the local level.

Communist Party: Japan’s oldest political party and definitely left of the CDP, though to what degree they’re actually communist in the 21st century has always been a matter of intense debate. See my article on why leftism failed in Japan.

While they attract a decent amount of local support in some areas, they hold just 10 seats in the House of Representatives and would need 223 seats to become the majority. It ain’t happening.

Democratic Party For the People: A new party formed in 2018, initially as a merger between the defunct Democratic Party and defunct Party of Hope. Yes, that was the actual name. This party eventually merged with the CDP in 2020 except for 14 members lead by politician Yuichiro Tamaki, who kept the DPFP name. They describe themselves as a more centrist alternative to the LDP, but their policy goals tend to be so vague and wishy-washy that they almost sound like a parody of centrists. One can only wonder how they even got 7 seats to begin with.

Reiwa Party: This joke of a left-wing party is widely mocked by practically everyone in Japan. It was founded by actor Taro Yamamoto, who is best remembered for appearing in Battle Royale. He’s one of the few examples of a Japanese celebrity becoming a politician, but that’s precisely why hardly anyone takes him seriously. Reiwa is basically opposed to everything the Japanese establishment believes in, which may resonate with a few Japanese hippies and radical leftists, but most of the public isn’t buying it. Good luck trying to square keeping Japan’s pacifist constitution, but getting rid of U.S. military bases for defense. Maybe Yamamoto-san thinks Kim Jong Un will stop launching ICBMs over Japan if he asks nicely.

Reiwa holds 3 seats. Give them time, I’m sure they’re just planning the long game.

Social Democratic Party: Formed from the ashes of the Japan Socialist Party when it died in 1996. They hold 1 seat. Irrelevant, just like the ideology it represents.

Sanseito Party: If you think I’m being unfairly mean to Japan’s crackpot leftists, don’t worry, the crackpot right-wing populists are also a pathetic joke too. The Sanseito or Political Participation Party was founded in 2020 on the basis that the COVID-19 pandemic was staged and that vaccines are a plot from the government to control everybody. Sanseito has a small degree of appeal with the Japanese equivalent of Alex Jones’ audience, but like the SDP, they only hold 1 seat. Also irrelevant.

What I’m watching — Terry Gilliam’s “Brazil” is still one of the best dystopian films

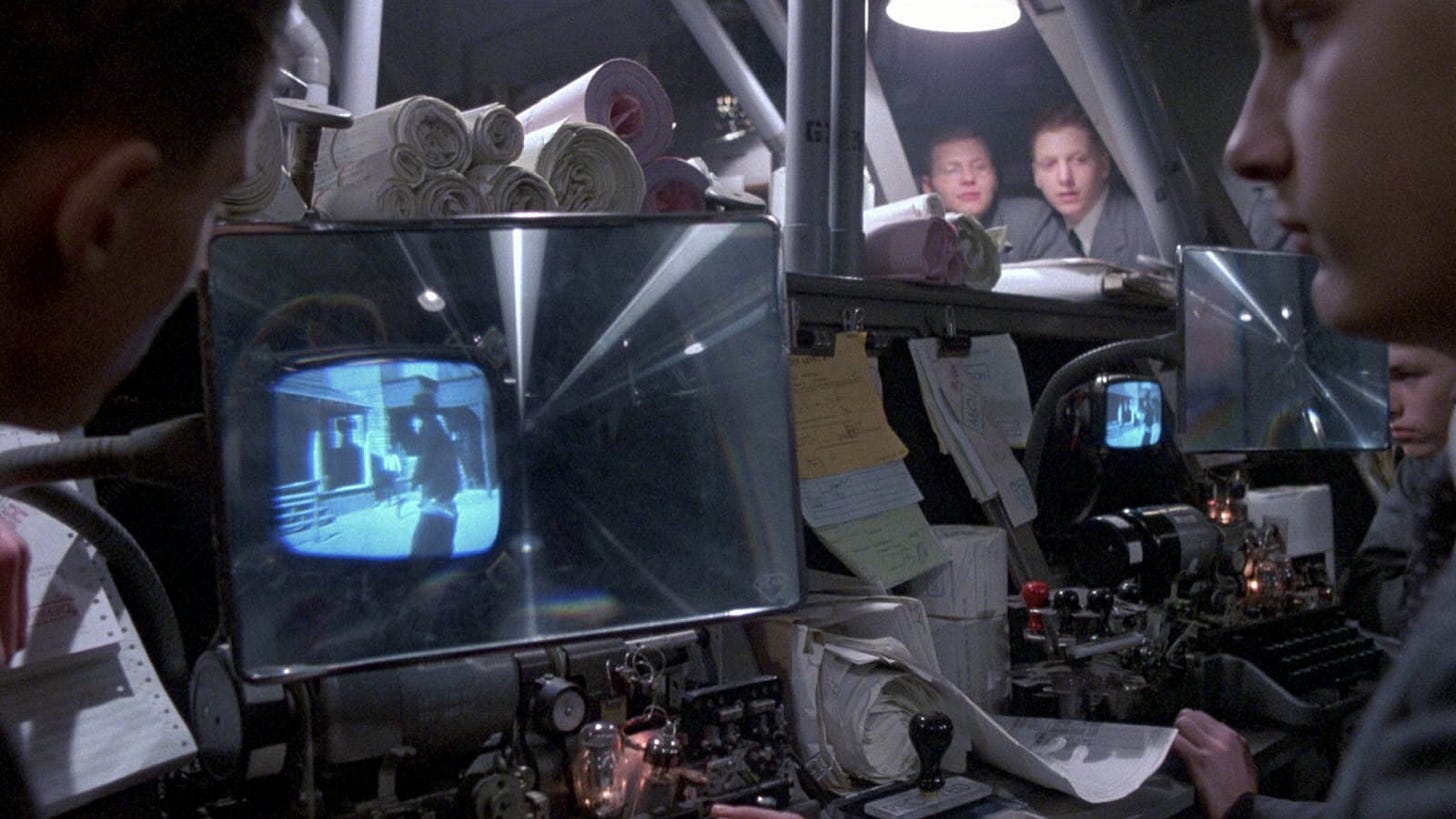

Despite being a cinephile, there are still plenty of gaps I’ve yet to fill. Terry Gilliam is one of them. The only film of his I had previously watched was Monty Python and the Holy Grail, but that’s obviously part of a larger franchise and quite different from his later work. As luck would have it, a friend gifted me a DVD copy of Brazil for my birthday, which I had always wanted to get to at some point anyways. I’ll eventually do a proper watch of Gilliam’s entire filmography in release order, which is what I tend to do with most directors, but for the time being this was an excellent introduction to his style.

Set in a dystopian 20th century, Brazil deals with the absurdities and horrors of bureaucracy. Virtually everything in this world requires paperwork to happen, down to simply repairing an apartment’s air conditioning. It’s to the point where repairing equipment without official state approval is illegal and those who attempt such unlicensed jobs are wanted criminals. Protagonist Sam Lowry is in the drecks of this as a middling government employee, but his worldview gradually unravels after he falls in love with a woman who previously appeared in his vivid dreams.

Many films have depicted dystopian societies, but Brazil easily ranks as among the best. Terry Gilliam intended to create a world that melded the sensibilities of past and future together, which is evident in Sam looking like a 1940s film noir protagonist but being surrounded by high tech computers and machines. Brazil is all about contrasts and contradictions. It has a thoroughly compelling aesthetic where everything manages to feel both clean and dirty at the same time, as well as modern and anachronistic. For that reason, the film has continued to aged beautifully over the years, inspiring everything from Tim Burton’s Batman to even the 1993 live-action Super Mario Bros. movie.

The fantastic production design is populated by an incredible cast of some of the finest actors of the decade. It was the breakthrough film for Jonathan Pryce, who succeeds in making the everyman protagonist someone you empathize with and want to escape from this nightmare. He’s joined by Katherine Helmond, Robert De Niro, Ian Holm, Bob Hoskins, and even returning Monty Python star Michael Palin who all turn in memorable performances. The only odd one out is Kim Greist as the main romantic lead. She had a relatively short acting career and is currently retired. Gilliam was reportedly not fully satisfied with Greist’s performance, but I thought she did a fine job despite having had less experience than many of the other bigger name actresses who were considered for the role at the time.

Some view Brazil as an anti-capitalist film, but I think that’s somewhat of an oversimplification. Terry Gilliam is a liberal, but more of an old school kind and has never come out as being opposed to capitalism. Screenwriter Tom Stoppard has described himself as a “small c” conservative libertarian and while there isn’t much information available on co-writer Charles McKeown’s views, none of his works suggest any real socialist bent either. Instead, Brazil is a greater commentary on general human themes and totalitarianism. Not to mention that Gilliam’s Monty Python roots make him no stranger to social satire and having a drive to lampoon practically every subject one can think of. Nearly 40 years later, Brazil is especially prescient in our modern age given the film’s exploration of technology running every aspect of daily life and how the state uses it to increase surveillance.

The film is frequently compared to George Orwell’s 1984, which was adapted to cinema the previous year in, ironically, 1984. Both have a number of similarities, but the kind of totalitarian societies they depict are quite different. 1984 is ostensibly the far bleaker film, but Brazil is arguably more terrifying in certain ways for how its initially comedic tone gradually devolves into an ending that hits you like a bag of bricks. Gilliam always believed his film had more believable humanity than Orwell’s story, which is also why he thinks his conclusion is actually more optimistic than many are usually lead to believe. Watch both as a double feature if you have no desire to be in a good mood on your Sunday afternoon.

What I’m listening to — Brahms’ Hungarian Dances are an easy introduction to classical music

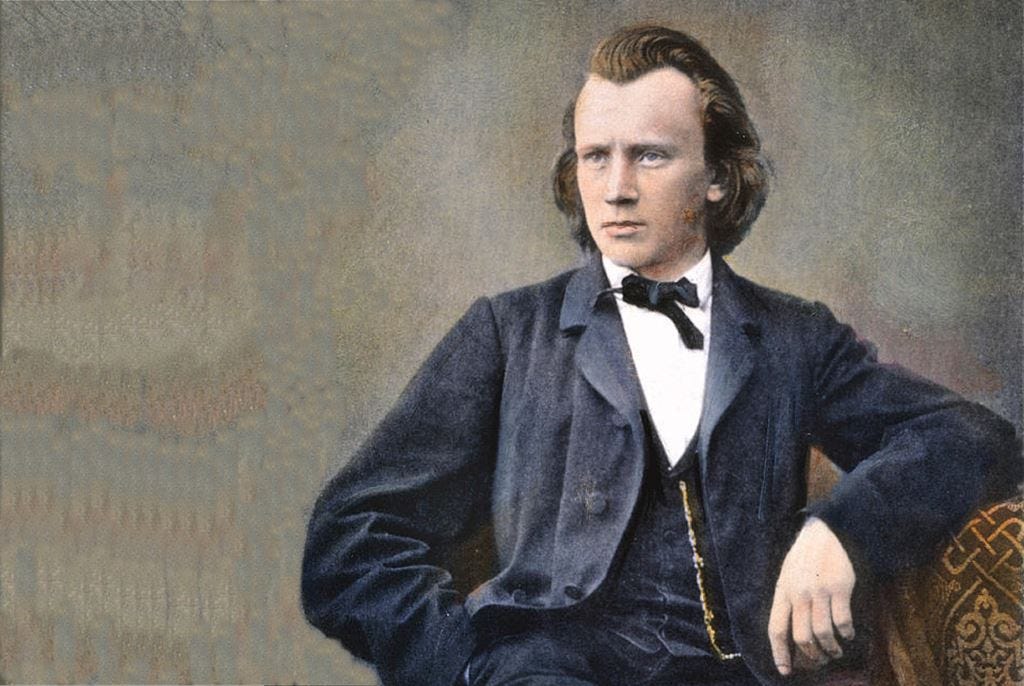

It’s been awhile since I last discussed classic music on Bonus Perspectives, so I’ve decided to return to the subject this week. Most consider Ludwig van Beethoven, J.S. Bach, and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart to be the big three of classical music, but if there’s a fourth spot to consider, it would definitely go to Johannes Brahms. Born in 1833, six years after the death of Beethoven, Brahms is an interesting bridging point between the Romantic era (1800-1910) of classical music to the modernism of the early 20th century.

He was caught in the middle of the so-called “War of the Romantics” which was a fierce debate among mid-19th century composers around what direction music should be taken in. While Brahms was ironically from the conservative school, his work in retrospect has been highly praised for its complex harmonic innovations, cross-rhythms, and skillful use of thematic variation. Since he combined these novel techniques with traditional classical forms of his predecessors like Beethoven, the music of Brahms often manages to be a beautiful combination of old and new. It still feels modern by today’s standards because so much of present-day music owes its inspirations to Brahms’ harmonic and rhythmic contributions.

Brahms is probably most famous for his Cradle Song, which has become the standard lullaby across the world. It’s surreal hearing it in its original form since it’s such a commonplace piece of music in daily life like “Happy Birthday” and “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star,” but that’s a testament to just how timeless Brahms’ melodies are amid his sophisticated technical achievements. His four symphonies and four concertos are of course all highly recommended, but if one wants to get into his music, I always fall back on the Hungarian Dances completed in 1879 as a tried and true favorite.

Few have heard all 21 Hungarian Dances, but listening to them in order demonstrates just how eclectic Brahms’ approach to composition was. Almost every piece is based on an existing Hungarian theme or local folk song, while Brahms’ signature approach to harmony and rhythm make the elements comes together in a way that guarantees no two dances sound the same. The most famous is without a doubt No. 5, which has been performed, covered, and sampled thousands of times for well over a century. My favorite is No. 4, which later became the basis for the main theme “Hope for the Best, Expect the Worst” from Mel Brooks’ criminally underrated sophomore film The Twelve Chairs.

No. 11, 14, and 16 are completely original, but one can really hear how Brahms takes inspiration from the existing folk music themes that comprise the rest of the dances to create something in a similar vein. With each piece typically ranging from two to five minutes each, the Hungarian Dances are a very accessible way for someone to get a feel for the basic structure of Brahms’ work and classical music as a whole. It’s no surprise that they’re constantly performed in concert halls across hundreds of countries, particularly as encore pieces due to their lively nature.

Originally composed for piano, Brahms only wrote the orchestral arrangements for Nos. 1, 3, and 10. Other composers such as Antonín Dvořák took it upon themselves to arrange the rest, which only adds to the various musical, historical, and cultural influences that surround the overall work. The Hungarian Dances are not just static compositions. They’re based on music that was already vintage in Brahms’ day reworked for a new audience, while other artists have continued to expand upon their themes via new arrangements and variations. The Hungarian Dances were also a huge inspiration for ragtime artists like Scott Joplin and James Scott, which lead to the eventual evolution of jazz and rock roll. It’s no exaggeration to say that modern music owes a major debt of gratitude to Brahms.

Recommended listening:

All 21 Hungarian Dances — orchestral arrangement performed by the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra

Hungarian Dance No. 1 - duet piano by Khatia Buniatishvili, Yuja Wang

Hungarian Dance No. 4 — solo piano by Barry Douglas

Hope for the Best, Expect the Worst — main theme to The Twelve Chairs composed by John Morris adapted from Hungarian Dance No. 4

Hungarian Dance No. 5 — duet piano by Lang Lang and Gina Alice

Hungarian Dance No. 5 — orchestral arrangement by Leopold Stokowski in one of his first recordings with the Philadelphia Orchestra in 1917

Hungarian Dance No. 6 — orchestral arrangement by the Frankfurt Radio Symphony

Hungarian Dance No. 7 — orchestral arrangement by the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra with solo violinist Maxim Vengerov

Bonus: An utterly fascinating audio recording from 1889 of Brahms himself playing a shortened version of Hungarian Dance No. 1. It was recorded by Thomas Edison’s assistant Theo Wangemann. The audio quality is very poor, but you can hear Brahms doing a self-introduction in German and some of his piano skills. The fact that Brahms lived long enough to see the age of sound recording is nothing short of astounding.