How Terrorism Killed Leftism in Japan

The story of the Red Army's decades of bloodshed and attempted revolution which ended in failure.

“I think Japanese people are even more apathetic about politics now than in the past …and I do think the actions of myself and others have contributed to that.”

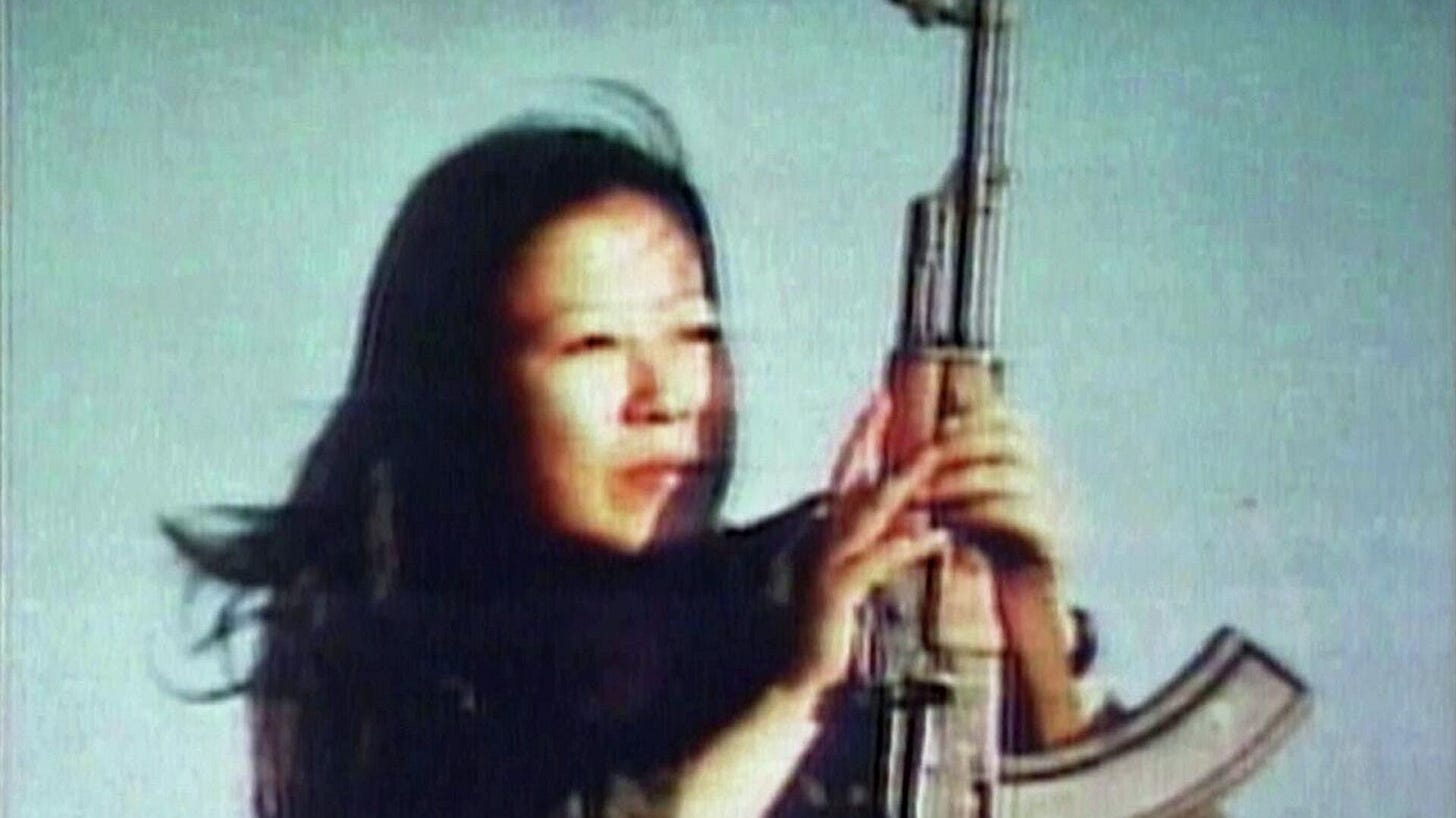

These were the words of former Japanese Red Army founder Fusako Shigenobu decades after she and her organization once established themselves as one of the most notorious terrorist groups in the world.

As radical communists influenced by the New Left movement of the 1960s and 1970s, the Red Army occupies a fascinating space in the political history of Japan. But while once regarded as among the most dangerous extremists of their era, there is now next to nothing left of them today.

In modern-day Japan, left-wing ideologies like socialism and communism have little resonance with the Japanese public. The Japanese Communist Party maintains some degree of influence on local politics, but it is a far cry from the ideals of a sweeping international revolution in solidarity with other states as envisioned by Marx and Engels.

Yet more than five decades ago, this was the dream of the Red Army and one they were willing to achieve by any means necessary. Their advocacy of revolution through terrorism and constant in-fighting, however, proved to be their downfall.

Events such as the Yodogo Hijacking Incident, the Asama-Sanso Incident, and the Lod Airport Massacre brought the group’s violent activities to international attention, which played a major role in left-wing movements failing to achieve success in Japan. Unattainable goals and internal divisions additionally made a single unified vision all but nonexistent.

While the Red Army was not the sole cause of leftism’s decline in Japan, it was certainly a catalyst that did no favors to the existing factionalism of Japan’s major left-wing political parties. The organization’s terrorism ultimately imparted a negative impression on the consciousness of the Japanese public which in the end chose to reject their murderous ideology.

The Birth of the Red Army

It is first necessary to define the name “Red Army” (Sekigun) itself, which is often used interchangeably for three separate, but related groups. In its earliest form, the organization was referred to as the Red Army Faction (Sekigunha), led by Takaya Shiomi in 1969. Members of the RAF joined forces with another group to become the United Red Army (Rengō Sekigun) in 1971.

A separate organization referred to as the Japanese Red Army (Nihon Sekigun) formed in Lebanon the same year by Takeshi Okudaira and URA member Fusako Shigenobu, who formally broke with them to lead the JRA full time in 1972. This article will refer to each group by their specific name when it comes to analyzing their respective activities, but it will employ the general term “Red Army” to refer to the overall movement as a whole.

The group’s original form, the aforementioned Red Army Faction, was essentially stripped of its relevance in the first year of its existence. It advocated “‘simultaneous, worldwide revolution’ through violent tactics, in the name of Third World and other oppressed minorities” and was linked to other New Left factions overseas.

The Japanese New Left movement was essentially analogous to its Western counterparts, but some members took things to even more bizarre extremes. Political activist and later terrorist Katsuhisa Oomori created the self-hating ideology of “Anti-Japanism,” which advocated for the eventual extinction of the Japanese race as a whole. While only the most radical of extremists subscribed to views like Oomori’s, such beliefs are said to have influenced the doomsday cult Aum Shinrikyo and their sarin gas attack in 1995.

Breaking off from the Japanese Communist Party in order to mobilize a younger student-led movement, the Red Army Faction’s initial key issue was the anpo security treaty between Japan and the United States which was set for renewal in 1970. Even further to the left than the JCP, the RAF engaged in assaults on government buildings and violent clashes with police. Poorly executed, it rapidly lost members due to arrests, which itself culminated in the imprisonment of its leader, Takaya Shiomi, after a failed insurrection against Prime Minister Eisaku Sato in November 1969.

Consisting mostly of university students, the RAF’s goals were lofty at best and a serious security threat at worst which made acceptance by the Japanese public unlikely from the outset. By 1970, Japan had the third largest GDP in the world and was experiencing unprecedented economic success. Moreover, the Japanese Socialist Party and Japanese Communist Party were weakened due to a lack of clear vision, which only solidified the power of the Liberal Democratic Party.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Foreign Perspectives with Oliver Jia to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.