Revisiting "The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles"

George Lucas' forgotten Indiana Jones show is a beautiful piece of 1990s television that adds to Indy's character and serves as an effective tool for learning history.

Just as with the Star Wars Expanded Universe, the Indiana Jones franchise has extensive media outside of the films. Since the 1981 release of Raiders of the Lost Ark, Lucasfilm has commissioned countless books, comics, and video games to extend the series’ lore and characters, but most of it remains largely unknown to the general moviegoing public.

While Star Wars lends itself to a virtually infinite amount of stories due to its huge universe which can go beyond the Skywalkers, there is far less to work with when it comes to Indiana Jones apart from its titular protagonist. Many are under the impression that only Harrison Ford can play Indiana Jones and that the franchise is unable to continue without him.

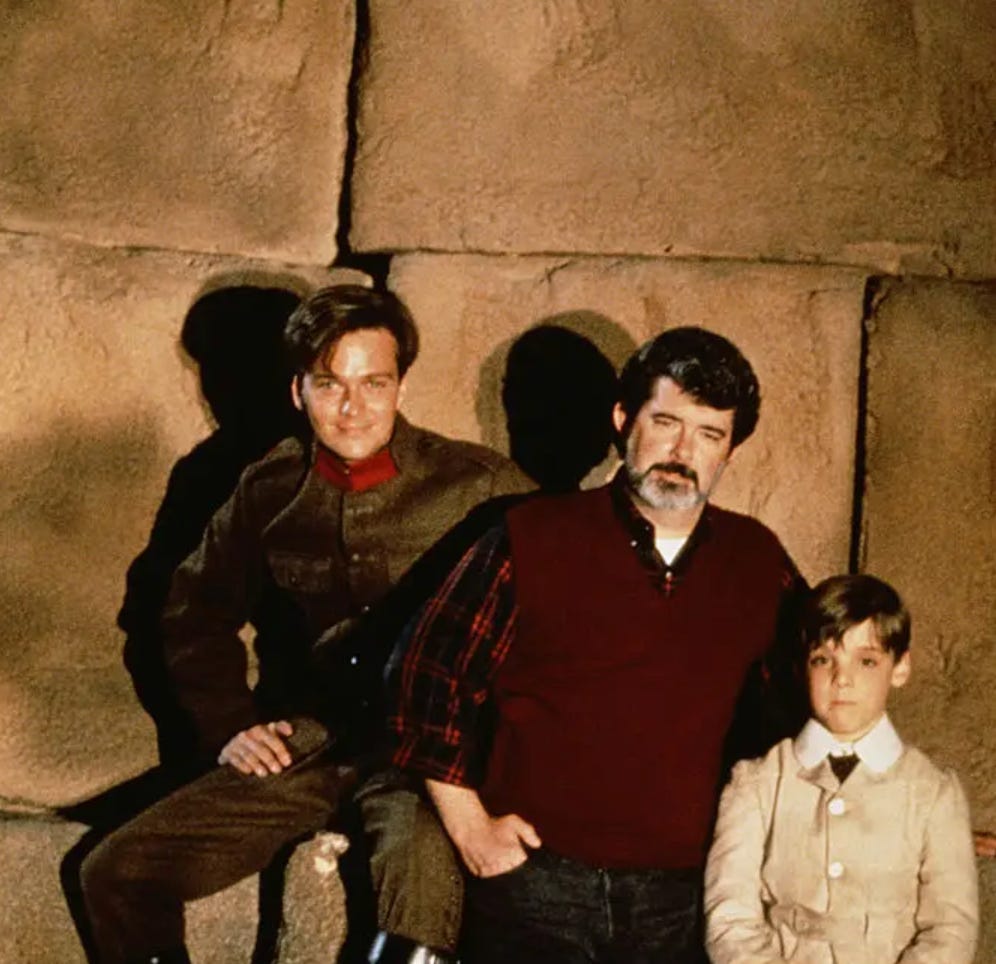

But what if the solution to this was not forwards, but backwards? That’s exactly what George Lucas’ 1992 television series The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles intended to do in exploring the childhood, adolescence, and early adulthood of Indy before he became the famous globetrotting archeologist we all know and love.

With the series now dusted off and and on Disney+ for a new audience to discover, it’s time to give this overlooked gem of a show the deep-dive it deserves.

Back to the Past

As viewers will remember, Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade opened with a flashback sequence of a 13-year-old Indy played by the late River Phoenix taking the Cross of Coronado from robbers in Utah. We learned where his hat and whip came from, as well as the origins of other aspects later seen in the character. Following the release of the film in 1989, George Lucas and Steven Spielberg tossed around ideas for a fourth. But as that project languished in development hell, Lucas decided that television would be a better medium for more stories and once again returned to his concept of a younger Indiana Jones.

While the show would flesh out Indy’s character, Lucas aimed for it to also be an educational program that could teach young people about 20th-century history. The format consisted of each episode featuring an elderly Indiana Jones in his 90s telling stories to his children, grandchildren, or even total strangers. The show would then flash back to the past and feature Indy either as a child aged 8 to 10 or as a teenager and young adult aged 16 to 21 before returning to the present with the character at 93 years old.

Indiana Jones here is a Forrest Gump-like character who appears to meet virtually every major figure of the 20th century from Pablo Picasso to Ernest Hemingway, as well as Sigmund Freud, Carl Jung, and Alfred Adler all in the same room at the same time. This led to many guest appearances by famous actors such as Max von Sydow and Tom Courtenay, while even big names like Catherine Zeta-Jones, Ian McDiarmid, and Daniel Craig lent their talents to the show.

While some of Indy’s encounters with these figures truly stretch the realm of plausibility even within the context of the show’s fictional universe, the results are still highly entertaining and one can’t help but marvel at George Lucas’ sheer passion for history. Each episode has its own director, including some veteran ones like Nicolas Roeg and Terry Jones, but Lucas’ fingerprints are extremely apparent. It’s clearly a show that could only have been made by him, and he would even cite it as an important learning experience for creating the Star Wars Special Editions and The Phantom Menace.

The three actors who play Indiana Jones all bring something unique and different to the role. Corey Carrier took on the youngest incarnation of Indy, having already been an established child actor. While Carrier was a few years older than the character’s actual age in the show, he does an admirable job of capturing both Indy’s passion for adventure, youthful ignorance, and tendency for reckless actions. If we compare him to how Jake Lloyd portrayed a nine-year-old Anakin Skywalker in The Phantom Menace, I find Carrier to be far more convincing in doing Indiana Jones at roughly the same stage in life. His episodes are often considered to be the weaker ones of the show, but there is still plenty to enjoy.

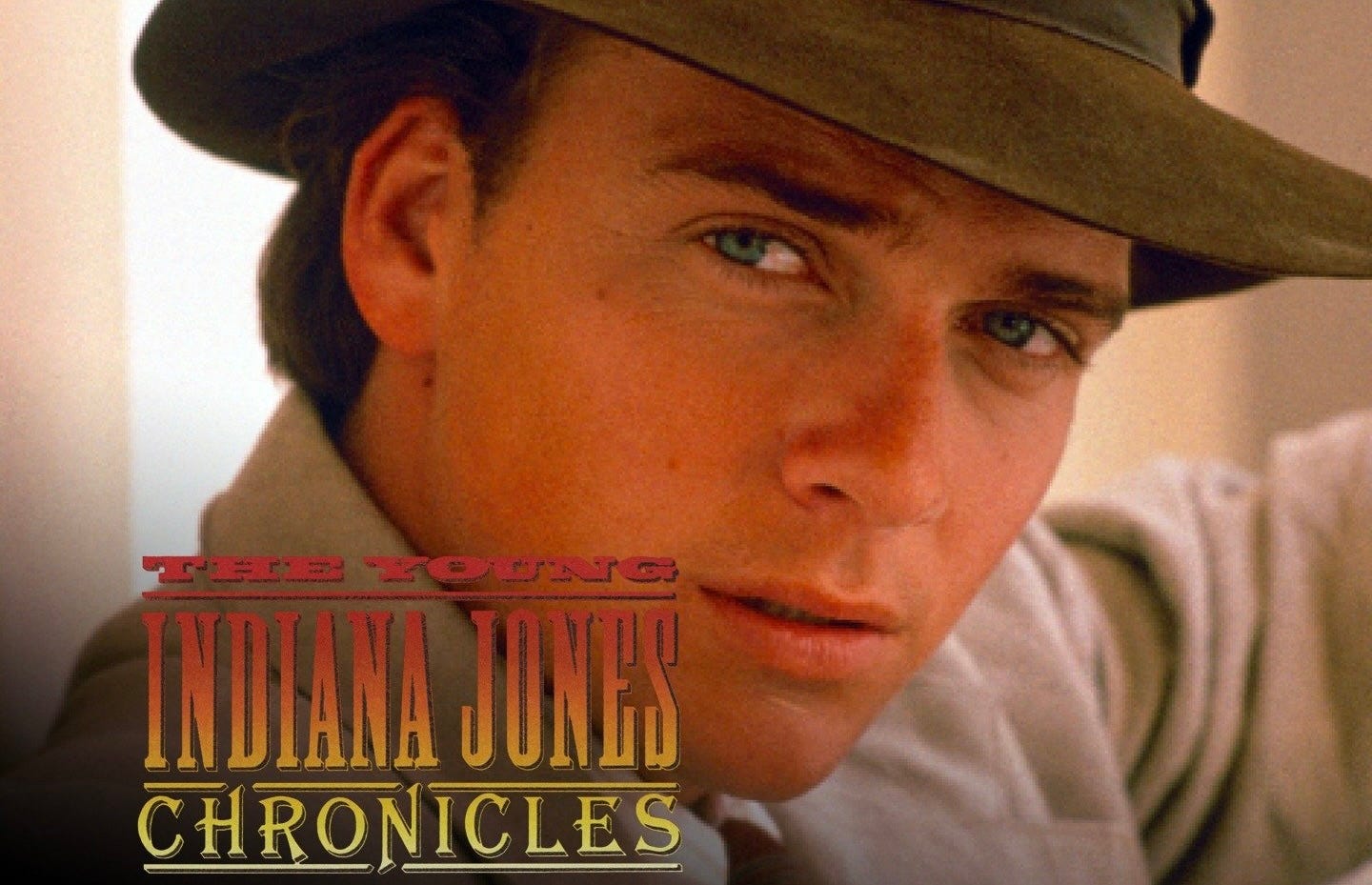

Sean Patrick Flanery, on the other hand, is definitely the highlight of The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles. Carrying on the bulk of the series, Flanery has the difficult task of convincing audiences that he’s playing a teenage and young adult version of Harrison Ford’s iconic character. It would be an intimidating role for anyone, but he knocks it out of the park. We get to see a satisfying character arc of Indy going from a normal high school student to a brutalized veteran of World War I, and it’s all thanks to the genuine charisma Flanery brings to the role. In addition to the brown fedora being a natural fit, he smoothly handles the increasingly complex action scenes the show required as it went on. If there was ever to be a new Indiana Jones film or television show, I’m confident that the now 57-year-old Flanery with his maintained physique and long career of action roles would be able to take over from Ford.

Capping things off, we have George Hall as the 93-year-old version of Indiana Jones who provides the bookends for nearly every episode of the show. Hall’s turn as Indy is slightly controversial among fans, as some believe that this elderly portrayal strays too far from the character’s roots. Personally, I like to believe that Indy did go on to have a quiet life in retirement with children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren. I don’t buy the idea that Hall is playing an unrealistic version of Indy in his nonagenarian years because with everything the character has been through, it’s perfectly reasonable to expect an old man who’s a little stubborn, but still full of wisdom to pass on to a new generation.

The rest of the main cast proves to be just as memorable and well-performed. Lloyd Owen does a phenomenal job as Indy’s dad Henry Jones Sr. with his mimicry of Sean Connery’s accent. The chemistry between him and Corey Carrier works beautifully, but Owen’s scenes with Sean Patrick Flannery are especially impressive considering that both actors are the same age. We’re also introduced to Indy’s mother Anna played by Ruth de Sosa and tutor Helen Seymour played by Margaret Tyzack, both key maternal figures who would shape the kind of man he would become. As hinted in The Last Crusade, we see that Anna Jones was largely what kept Indy and his father on decent terms, but her death created a major wedge between them.

Helen Seymour, on the other hand, is an original character. We first see her as a strict tutor who takes great lengths to educate Indy despite their initial dislike for each other. But as the series progresses, their relationship evolves into one of mutual respect and affection. Seeing both Carrier and Flanery interact with her is one of the great joys of the series, and all of it provides vital character development for Indy. Through his parents and tutor, we get a sense of what shaped his desire to see the world and strive to become a learned scholar.

Adventure of a Lifetime

The show chronologically begins in 1908 with Henry Jones Sr. being invited to go on a two-year trip of the world to lecture at various universities and educational institutions. Accompanied by his mother and tutor, it’s the chance of a lifetime for the eight-year-old Indiana Jones to learn the languages, cultures, and histories of various countries along the way. From meeting T.E. Lawrence in the Egyptian desert to bonding with Leo Tolstoy in the Russian countryside, Indy goes through highs and lows that prove to be pivotal experiences for the young boy. This is the portion of the series focused on Corey Carrier, which as previously stated, some believe to be its weakest part. While I agree that Sean Patrick Flanery’s episodes are generally more interesting, I still never felt that I was wasting my time in watching the stories featuring Indy as a child.

In “Vienna, November 1908,” Indy falls in love with the daughter of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. It’s a relationship that’s ultimately doomed to fail, but a memory he carries for the rest of his life and the start of his romantic adventures with many women. In “British East Africa, September 1909,” we see him learning how to shoot a gun for the first time with Theodore Roosevelt and later convincing the former U.S. president to value the sanctity of endangered animal life. But for me, the best episode of this era is the television movie Travels with Father. Indy and Henry Jones Sr. are forced to be together on a trip in Greece while his mother and tutor are away. It’s one of the few opportunities for both to bond with one another, and a rare moment of fatherly love Henry shows toward his son before their eventual estrangement.

After the family returns to America, Anna Jones dies off-screen from scarlet fever, which leads to Indy and his father growing further apart. By 1916, Indy has a steady high school sweetheart and deals with the typical troubles of boys his age, but a trip to Mexico during spring break vacation will change his life forever. After being kidnapped by Pancho Villa’s men, he meets and befriends a Belgian named Remy Baudoin. The two briefly take part in Villa’s revolution, but become disillusioned when they realize it isn’t their fight. Remy chooses to return to his country to fight the Germans in World War I, and Indy resolves to go with him despite the U.S. having yet to enter the conflict.

The next three years are a pivotal learning experience for Indy. WWI makes up the majority of The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles, and it’s where the series truly becomes a masterful piece of television. Indy takes part in some of the most brutal moments of the war like the Battle of the Somme and Battle of Verdun, while also experiencing being a prisoner of war and seeing further action on the African front. George Lucas’ affinity for history is apparent with the appearances of key figures like Charles de Gaulle and the Red Baron, while the show pulls no stops in depicting the brutality of the fighting with its high production values.

While the Corey Carrier episodes focused on the character’s childlike innocence, the Sean Patrick Flanery episodes are appropriately about Indy losing that innocence and becoming the adult we later see. Indy lies about his age when applying to join the Belgian Army and uses the alias Henri Defense, but the recruitment office takes him anyways due to a shortage of men.

In “Somme, Early August 1916” and “Germany, Mid-August 1916,” Indy bears witness to the sheer brutality of trench warfare. One particularly chilling scene depicts a fellow soldier begging Indy to give him his mask when the Germans engage in a mustard gas attack, only to die before his eyes. In the episode “Verdun, September 1916,” Indy becomes a mail courier dispatching messages to the front via motorcycle, but is faced with a dilemma when one written order would send the French and Belgians into a total slaughter by the Germans.

The following episode “Paris, October 1916,” however, takes things in a different direction with the 17-year-old Indy beginning his first sexual relationship with none another than Mata Hari while on leave in Paris. He learns the realities of adult romance the hard way as the exotic dancer has many lovers and is also under suspicion for being a German spy. After parting with her, Indy is transferred to Africa where some of the show’s best action set pieces are seen in the television movie The Phantom Train of Doom.

Here, Indy is forced to work with a gang of elderly soldiers who impart on the young lieutenant the importance of intelligent strategy over brute force while on a dangerous mission to blow up a German train. The lessons continue when Indy leads a group of Congolese soldiers in “German East Africa, December 1916” and learns about compassion for the enemy from Albert Schweitzer in the follow-up “Congo, January 1917.”

The war years continue for Indiana Jones, but his performance on the front impresses his superiors. Instead of working as a combat soldier, Indy is now a spy tasked with covert intelligence missions. James Bond was always one of the main inspirations for the franchise, and George Lucas is able to bring the character close to those roots with these episodes.

By amusing coincidence, Daniel Craig even guest stars as the German officer antagonist of the television movie Daredevils of the Desert, a thrilling Lawrence of Arabia-influenced epic that features exciting calvary scenes and some hilarious romantic chemistry between Indy and a beautiful spy played by Catherine Zeta Jones. Yeah, you definitely have to see this one to believe it.

This era also leans into the show’s strangest moments. “Prague, August 1917” sees Indy being tasked with receiving a very important phone call from an informant at a specific time at a specific place, but the entire episode is one long comedic romp where nothing goes right for him. From vital documents being blown out the window to being forced to confront the absurdities of bureaucracy, Indy experiences a Kafkaesque nightmare until he meets, well, Franz Kafka.

In “Transylvania, January 1918,” Indy investigates the disappearance of disappeared spies in Romania, only to come face to face with a literal vampire who can raise dead soldiers from the grave. This episode is notable because it’s the only one to introduce supernatural elements while the rest of the show keeps things largely grounded. The Indiana Jones franchise is obviously no stranger to these concepts, but it admittedly feels somewhat out of place amid a series that typically strives for realism.

The last era of Young Indiana Jones sees WWI coming to an end and Indy needing to decide what direction to take his life in. A highlight here is the television movie Treasure of the Peacock’s Eye which is the closest the show gets to be a globe-trotting adventure like the films. Remember that large diamond which appeared in the beginning of Temple of Doom? This episode explores the origins of where that treasure comes from and the long history behind it. It begins with Remy and Indy finding a map off a dying soldier in the last hours of WWI, which leads to a series of clues that hints at the diamond’s final location. Yet while Remy is hungry for treasure, Indy gradually realizes that he cares more about archeology and the preservation of history.

Upon returning home, Indy and his father finally come to blows. Despite having not seen each other for years, Henry Jones Sr. appears to show little interest in what his son experienced during the war and continues to act as if nothing ever happened. This eventually culminates in a heated and heartbreaking fight, with Indy claiming that his father never cared about him or his mother. Henry would later apologize and express his relief that his son returned home safely. But Indy’s decision to study archeology at the University of Chicago instead of going to Princeton at his father’s urging once again drives a wedge between both men. As Indy would later state in The Last Crusade, neither would say much to each other over the next 20 years. A few other episodes bring the series to a rather anti-climatic close afterward, but the emotional highs really make this point feel like the real end.

This summary only scratches the surface of everything Young Indiana Jones covers, but it should provide an idea of how the series blends both history and lore around the titular character into something truly special. As a middle school student, I remember borrowing the DVDs from my local library and being utterly captivated by the WWI episodes of the series in particular. While I was too young to understand every nuance, it was the first time I learned about the war in any great detail and it even helped me ace a few exam questions when I took American history courses in high school.

Lucas clearly strove for realism with the uniforms, weapons, vehicles, and battlefield set pieces, while the proceedings are carried by Sean Patrick Flanery’s incredible performance. Young Indiana Jones shows great appreciation and nuance for other countries and their people, whether it’s in the rural countryside of Italy or a remote island off the coast of Papua New Guinea. It never attempts to assert any kind of cultural superiority, and that’s a big reason why the series has aged so well over 30 years later. I certainly learned many new things upon rewatching and became aware of many important historical figures I previously had no knowledge of. If you have even a passing interest in history, this series will only be all the more rewarding.

Young Indiana Jones taking place before the films naturally means that it has all the tradeoffs of being a prequel. We know that none of the girls Indy hooks up with will ever truly be the one for him, and having the knowledge of where he’ll eventually be decades later means that it’s obvious he’s going to survive all the dangerous scenarios. On the other hand, seeing that Indiana Jones was a WWI veteran puts the films in a new light, illustrating where his combat experience and courageous spirit came from. We also get to see how Indy learned to be somewhat of a playboy with women both with short flings and serious relationships, which also makes his cynicism toward romance as an older adult more understandable. With Young Indiana Jones, it’s not the outcomes that are most important, but how Indy got there which matters.

Sparing No Expense

Each episode of The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles cost roughly $1 million to make. A paltry sum in 2023 to be sure, but such a budget made it one of the most expensive television shows of its day long before something like The Mandalorian became a viable model in the modern age of streaming. The high production values are extremely apparent with each episode being filmed on location. When Indiana Jones and his family visit China, everything is actually shot in China. When we see shots of the African savannah, it’s the result of the film crew having spent weeks scouting for the right locations.

The various battlefield scenes required extensive sets and props, with a ton of practical effects used to generate the explosions. The series being shot on 16 mm film helped to lower the costs, but Young Indiana Jones was also a pioneer for being an early adopter of digital effects. George Lucas would employ similar tactics for The Phantom Menace, to the point of even reusing many of the same crew members.

Sound-wise, the music of Young Indiana Jones is just as richly crafted as its cinematic big brother. While the John Williams Raiders March theme isn’t used, the new main theme composed by Laurence Rosenthal pays tribute to it with similar melodic language. Rosenthal and co-composer Joel McNeely strove to ensure that each episode’s score reflected the eclectic cultures and environments Indiana Jones would find himself in. Both additionally weaved in existing classical music themes to create a soundscape appropriate for what one would hear in the early 20th century.

As an example, Rosenthal’s score for “Barcelona, 1917” contains numerous references to the Ballets Russes of Rimsky-Korsakoff’s Scheherazade due to the episode’s main plot structuring around Indy disguising himself as a dancer of that production while on a mission. It also features other homages to the ballets of Tchaikovsky and Stravinsky, in addition to Spanish corrida tangos reflective of the Barcelona setting. It’s the kind of intelligently composed score we rarely see in film or television these days, but just another aspect of why Young Indiana Jones was so special. The scores to select episodes were collected across four CD soundtrack releases. While that still only covers a small portion of the entire show, what’s included is excellent stuff regardless.

Young Indiana Jones as a whole spawned a wide amount of extra media, which perhaps isn’t too surprising given George Lucas’ strong emphasis on merchandising. Like Star Wars, there was no shortage of memorabilia such as T-shirts, posters, and a trading card game, while even more unorthodox items like Dixie Cups and Hallmark birthday cards were sold to the public. A long-defunct fan site catalogued some of these rare treasures, but there’s little information available on them. Like most media franchises in the 1990s, Young Indiana Jones also received the video game treatment with predictably awful results.

Instruments of Chaos starring Young Indiana Jones was a truly dreadful Sega Mega Drive game with punishing difficulty and unresponsive controls, making it a contender for one of the worst titles of the system’s library. Ironically, the video game adaptation released for NES two years early in 1992 fares far better and is actually quite playable. While no masterpiece, it’s probably the best Indiana Jones game for the system and does a decent job being an engaging platformer with a variety of weapons and items at the player’s disposal. A game for IBM computers was planned, but ultimately didn’t come to fruition. The designer who was supposed to produce the title has a rather humorous story on his blog of not recognizing Sean Patrick Flanery when he stopped by the office.

A short-lived comic book series adapted select episodes from the show, which featured a few differences from the original teleplays. The United Kingdom even had a spin-off comic strip series, though this did not last long either. Random House and Fantail Books additionally published novelizations aimed at younger readers in the U.S. and U.K., respectively. They provide some extra details such as Indy’s inner thoughts, but are mostly superficial when compared to the show.

A completely different series of original Young Indiana Jones novels began releasing even before the show aired, and they take place in between the Corey Carrier and Sean Patrick Flanery episodes. These 16 books are largely forgotten by Indiana Jones fans today, but like the television series, they aim to both educate audiences about history and expand the lore of the franchise. There’s even one where Indy and Miss Seymour find themselves aboard the Titanic after having lunch with Sherlock Holmes author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Is there anything in the 20th century this kid didn’t experience?

The most notable book from this period is The Mata Hari Affair, the only novel aimed at adult audiences. Author James Luceno, whom Star Wars fans will know for his excellent EU books like Labyrinth of Evil and Darth Plagueis, incorporates the same degree of high detail and knowledge of canon with Indiana Jones. Adapted from the Verdun and Paris episodes, it’s obvious that Luceno both watched the show and did extensive research on WWI. He doesn’t hold back on depicting the sexual moments between Indy and Mata Hari, while the latter character actually ends up being more sympathetic now that her perspective is also shown. The book also reminds us that despite everything Indy has been through until this point, he’s still a scared teenager learning his place in the world. Publisher Ballantine intended for The Mata Hari Affair to be the first of an entire series of Young Indiana Jones novels for adult audiences, but none were ever produced due to the show’s abrupt cancelation.

Fading Into History

This brings us to the obvious question. With so much care and attention put into The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles in addition to its expansive amount of extra media, why did this show ultimately fail? The best answer is that it was simply too ambitious for its own good. George Lucas knew that the scope of the television series would be massive and treated production as if it was for one large film. Initial writing, filming abroad, and editing took over two years, which required a wide pool of talent. American television network ABC financially backed the project because of Lucas’ name, but they faced difficulties in successfully advertising it.

While Young Indiana Jones undoubtedly had some of the best people in the industry working on it and high production values, Lucas’ main goal was to create an educational series. Those hoping for a nonstop action-adventure romp like the film trilogy would likely be disappointed and ABC wasn’t sure how to get around this problem. Though the pilot television film Indiana Jones and the Curse of the Jackal garnered decent ratings, critics believed the history content was too heavy-handed. ABC cut the first season short after only six episodes, despite dozens of hours of completed material already being in the can.

The network attempted to boost ratings during season 2 by bringing Harrison Ford back for a two-hour special episode entitled Young Indiana Jones and the Mystery of the Blues on March 13, 1993. While George Hall provided the opening and closing segments like usual in overseas airings, Ford played a middle-aged Indiana Jones in 1950 escaping pursuers in the snowy Wyoming mountains for the American broadcast. Yet this ploy didn’t succeed, and ABC canceled the show in the same year. Some remaining episodes were later edited together into four television films that aired on ABC’s Family Channel from 1994 to 1996, bringing The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles to its official end.

George Lucas had far bigger plans for Young Indiana Jones, with dozens of unproduced scripts intending to explore events and locations referenced in the show, but not yet seen. More tragic is that characters like René Belloq and Abner Ravenwood were supposed to appear in these episodes, providing even more direct connections between the television show and the films. Could it have saved the series from being axed? Likely not, but Lucas himself admitted that he made Young Indiana Jones as a passion project and cared very little about the concerns of television networks.

Re-edits and Contradictions

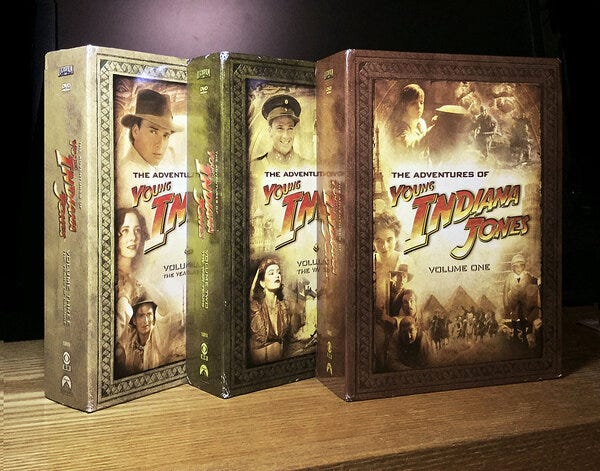

Just as he did with the Star Wars Special Editions, Lucas returned to the editing chair with The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles in 1999. Select episodes of Chronicles had previously been released on VHS and LaserDisc in various parts of the world, but this new edit aimed to rearrange the entire show into chronological order. This included every unaired episode, which ultimately resulted in 22 “films” rebranded with the rechristened name of The Adventures of Young Indiana Jones.

With the original movie trilogy, Lucas initially intended to release a 25-volume VHS set entitled The Complete Adventures of Indiana Jones, but only 12 of the re-edited Young Indiana Jones films made the cut, all of which were Sean Patrick Flanery’s episodes. The missing chapters aired on ABC in 2001 under the new Adventures name, but it would take until 2007 and 2008 for the entire series to be released on DVD as a tie in to Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull.

The differences between The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles and The Adventures of Young Indiana Jones are numerous, with some being for the better and some being for the worse. The show being restructured into chronological order provides a more satisfying arc of character growth for Indy. Chronicles would constantly jump around the timeline, making him seem less mature in some episodes despite having been through harrowing events in other episodes that aired previously but took place later. Other minor changes such as some characters having their dialogue re-dubbed and a couple of scenes slightly altered are largely inconsequential.

While things are more coherent in Adventures, it’s very obvious when new footage is inserted. Corey Carrier will jarringly become older in the second half of the same film, only to go back to being younger in the next one. Even Sean Patrick Flanery can’t escape putting on a few years, while it’s abundantly clear when stand ins are used for actors who couldn’t return to play their parts. As an example, this bridging segment for the first newly-edited chapter was actually filmed in Tunisia when George Lucas was doing The Phantom Menace and it isn’t fooling anyone.

While some of these films do pair episodes with one another nicely, such as Trenches of Hell and Demons of Deception, others are less successful and actually introduce continuity errors. Passion for Life combines “British East Africa, September 1909” and “Paris, September 1908.” As originally aired in Chronicles, the dates clearly show that the Africa episode takes place one year after the Paris episode, but the Adventures film places the Africa story before Paris and changes the date to September 1908. This doesn’t make sense, as the real Theodore Roosevelt made his expedition to Africa in 1909 just as Chronicles originally depicted. The man behind this blog has even more esoteric Indiana Jones knowledge than I do, and I don’t envy him having tried to come up with a coherent timeline for the franchise amid all the retcons.

Is Old Indy Still Canon?

The most obvious cut, however, is the absence of George Hall’s Old Indy bookends, and it’s indeed a big one. To this day, Indiana Jones fans hotly debate whether or not these segments still officially “count” as they were removed for the Adventures re-edit and are seemingly contradicted by Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (and possibly Dial of Destiny, but that’s a topic for another article once the film is out). Since these bookends were written and filmed long before the establishment of Indiana Jones marrying Marion Ravenwood and having Mutt Williams as a son, there’s certainly some inconsistencies that are hard to square.

For starters, Old Indy is shown to have an adult daughter named Sophie. George Lucas initially wanted a daughter, not a son, to appear in Crystal Skull, but Steven Spielberg vetoed the idea since he felt it was too similar to his Jurassic Park sequel The Lost World. It isn’t clear if this would have been the same character, but Indy does mention having several children in these segments. With Marion being in her late 40’s by the end of Crystal Skull upon marrying Indy and past the age of natural childbearing (there would have been few real options for surrogacy with 1950s technology), the only way to explain this contradiction is if Indy either had children with another woman or more likely adopted them later in life.

Despite this, there has never been any official indication of the Old Indy segments not being canon either. Leland Chee, the man responsible for managing both Star Wars and Indiana Jones canon, stated in 2008 that he did not receive orders from Lucasfilm to treat the George Hall material as non-continuity. If we take this as true, it is likely a similar situation between the 2008 Clone Wars animated series and the old Star Wars EU which often were in contradiction with each other, though the former always took priority. As another piece of evidence, even the Adventures of Young Indiana Jones re-edits feature the hands of an elderly Indiana Jones closing his diary at the end of each episode when the credits fade to black and white. So while it’s possible that not every aspect of the Old Indy segments is still canon, Indiana Jones living to old age probably still is. As of now, the wiki still includes them as part of the character’s biography, though of course don’t view that as an official source.

If one must create a headcanon, my stance is to view The Adventures of Young Indiana Jones as how Indy’s experiences “actually” happened, while The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles is Indy as an elderly man telling stories about his past to his relatives and children, biological or otherwise. As memory fades with old age, not every single detail is correct, but Dr. Jones still has a sharp mind and the overall gist is largely true. You can of course ignore the Old Indy segments entirely, but I like to imagine that after a lifetime of adventure, Indiana Jones was able to achieve the quiet life in retirement he deserved. A fan-made YouTube channel entitled “Young Indy Restored” uploaded every episode and incorporates the Old Indy bookends with the higher quality footage of the Adventures DVDs, making it the perfect option for those who wish to see the show in its original format.

The Legacy of Young Indiana Jones

Despite being a labor of love from George Lucas and a part of one of the most beloved film franchises of all time, time has given The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles a decidedly mixed legacy. Even after its extensive history of re-edits for home video, most fans of the Indiana Jones movies aren’t even aware that this show exists. But then again, I don’t think most are aware that there’s media outside of the films to begin with.

While Lucasfilm and Disney make sure the public never forgets about Star Wars with a nonstop flow of new television shows, books, comics, and video games, Indiana Jones has been a dormant franchise until this year with the arrival of the fifth film. After the hype around Kingdom of the Crystal Skull died down in 2008, little notable media around the series came out apart from one novel and a couple of video games in 2009. Rob MacGregor, the author of several Indiana Jones novels, has stated that Lucasfilm essentially viewed his work as marketing items and that their contents were never taken very seriously.

With that said, Young Indiana Jones is certainly canon. Crystal Skull features one scene where Indy tells Mutt that he rode with Pancho Villa and essentially summarizes the events of the Mexico episode. Coinciding with the release of the film was also a book entitled The Lost Journal of Indiana Jones that made extensive references to the show, confirming that its events did indeed happen. It remains to be seen how The Dial of Destiny will address Young Indiana Jones, but the franchise under George Lucas certainly did not consider the series to be inconsequential or unimportant.

Reactions from the Indiana Jones fanbase, however, are more divided. While I’ve always been a huge advocate of Young Indiana Jones both as a longtime fan of the franchise and as a history buff, that won’t necessarily hold true for everyone. Common criticisms against the show are that it focuses too much on being “edutainment,” is too separate from the films, and that it strays too far from what the character should be. Even as a fan, I can acknowledge the series having dozens of directors can create a disjointed feel and uneven tone at times. It won’t appeal to everyone and coming in with the wrong expectations is sure to lead to disappointment. For this reason, it is perhaps not too unsurprising that Young Indiana Jones is not the famous beloved television classic that George Lucas intended it to be.

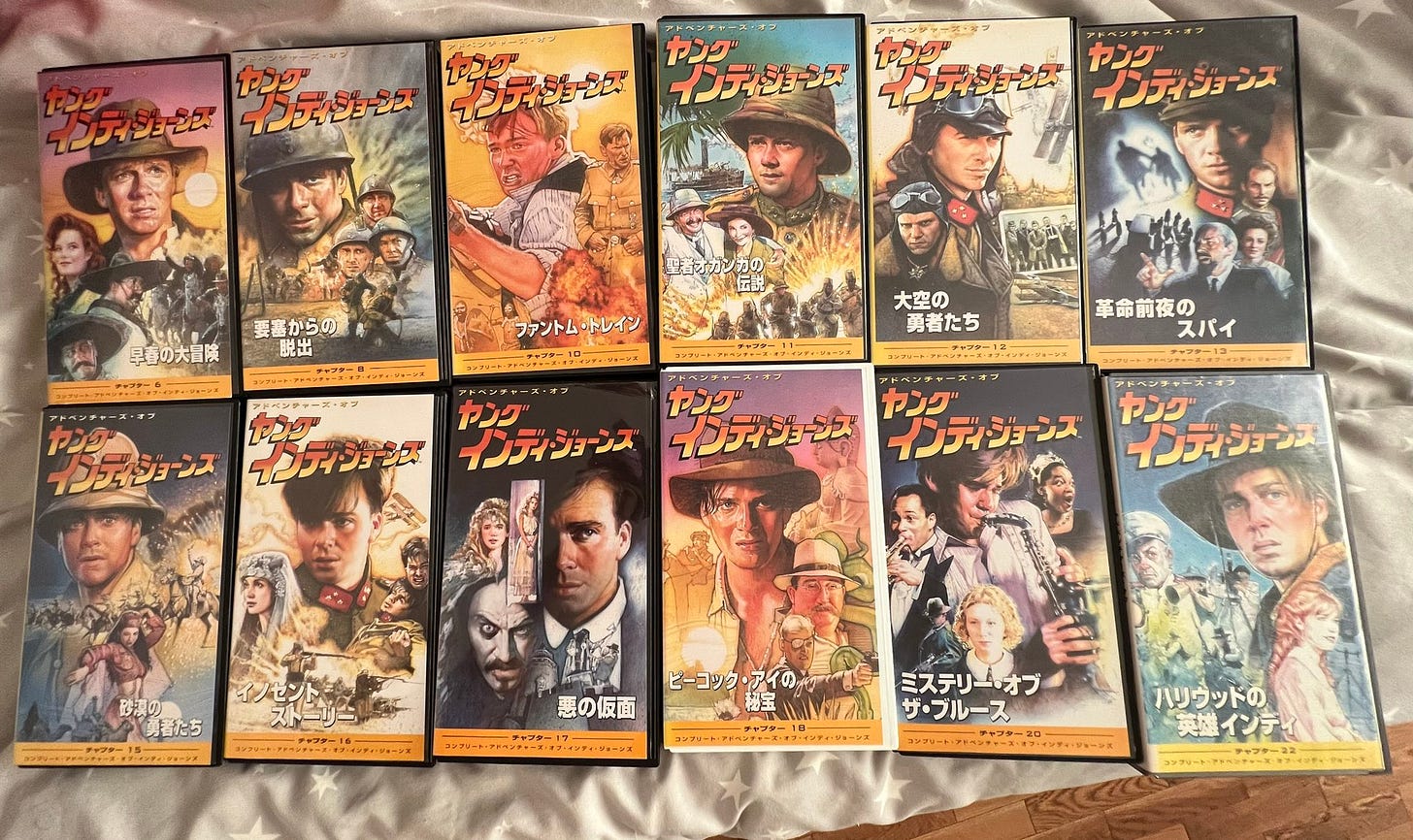

Another barrier to Young Indiana Jones in this day and age is its official availability. While the entire series is on DVD in three beautifully-crafted volumes with over a 100 documentaries covering each episode’s historical aspects, they remain exclusive to North America and were never released overseas. I live in Japan and despite Young Indiana Jones having seen pretty decent success here with a variety of translated media, the only official release in this part of the world is still on VHS/Laserdisc and it’s incomplete. In order to show this series to my girlfriend who only speaks Japanese, I had to track down the 12 tapes from the Adventures re-edit and get a VHS player, while a few other episodes from the Chronicles broadcast have been uploaded by Japanese fans online. I imagine that the situation in other countries where this show aired is even more dire, which is a real shame given the international appeal of Indiana Jones in the first place.

As a tie-in with The Dial of Destiny, Disney quietly made The Adventures of Young Indiana Jones available for streaming on Disney+ in May 2023, but only in the U.S. and with next to no advertising. The distribution rights to the Indiana Jones films and television series remain in Paramount’s hands, which severely limits where and how the franchise can be released. One can only imagine that the rights situation for Young Indiana Jones is very complicated and even using a VPN overseas provides no extra language options on the U.S. Disney+ stream. It was always my hope that the latest film would revive interest in the series, but the powers at be have seen to it that Young Indiana Jones will likely continue to languish in obscurity.

Prospects for the future of Indiana Jones as a whole do not look very positive either. I was always skeptical of the concept for a fifth film and my worst fears have seemingly been confirmed by the negative early reviews which came out last month after its Cannes premiere. The Dial of Destiny is one of the most expensive films ever made at $300 million dollars, and it will take a miracle for it to merely break even when it releases. Indiana Jones with Harrison Ford ending on such a critical, and likely commercial failure is not the conclusion that anyone wanted, which will only be further proof that Disney is out of touch with the legacy fans of these franchises.

Reports emerged last year that a new Indiana Jones prequel television series focusing on Abner Ravenwood was in development for Disney+. The history between Indy and his former mentor has always been hinted at in various stories, but never explored in full detail. This could have been the prime opportunity to continue where George Lucas left off with the original Young Indiana Jones series, but the most recent reports state that Disney chose to shelve plans for the new show to focus exclusively on Star Wars content. When you consider this and the flop Dial of Destiny is likely to be, it’s hard not to write off Indiana Jones as a dead IP apart from the upcoming Bethesda video game.

But given Disney’s generally mediocre track record with Star Wars shows, perhaps it’s for the best that it quit with Indiana Jones before it even started. The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles is the result of George Lucas’ pure creative vision, and a continuation couldn’t work without his involvement. It exists because he had the drive to create an ambitious, international series that he wanted to come to fruition regardless of how commercially successful it would be. Such big-budget projects that exist purely for artistic reasons and not profitability are utter anathema to today’s world of film franchises. Young Indiana Jones could not have happened outside of the era it came out in.

While it will always be disappointing that Young Indiana Jones never reached its full storytelling potential, what we do have is to me among the finest hours of 1990s television ever produced. In gradually showing how Indiana Jones went from a curious young boy to a hardened WWI veteran to the cynical whip-cracking adventurer we see at the beginning of Raiders of the Lost Ark, The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles does what a good prequel should do in expanding and enhancing series lore.

Whether you decide to watch the series in its original Chronicles broadcast format with the ambiguously canon Old Indy segments, its chronologically streamlined home video re-edit via Adventures, or simply decide to pick and choose what episodes seem interesting, you won’t find anything like it anywhere else. Indiana Jones may be the best adventurer to hit the silver screen, but how he got there via the smaller screen is just as compelling.

This is a better ad for the show than anything Disney could ever try to get people to watch it on Disney+.

I remember watching a huge chunk of the show back when I was 14 but I stopped watching and never returned to it, I think I know what I'll be spending my summertime with.