Remembering My Father Hong-Guang Jia (1954-2021)

A tribute piece to my late father who would have been 70 years old today.

Like most Chinese children during the Cultural Revolution, my father was mobilized to do manual labor.

For a brief period, he ended up working in a factory which required him to operate dangerous machinery. He nearly sliced the fingers off his right hand, but narrowly avoided permanent injury.

If he lost the use of his right hand, he never would have been able to hold a violin bow and take music lessons from his father.

If he did not learn music, he never would have been able to get a job at the Peking Opera as a violinist and earn a better living than most people around him.

If he did not join the Peking Opera, he never would have been able to enter the Central Conservatory of Music, China’s top music academy, when the Cultural Revolution had ended.

If he did not enter the Central Conservatory of Music, he never would have received a music scholarship from Yehudi Menuhin, one of the greatest violinists of the 20th century, and go to Europe to further his studies.

If he did not go to Europe, he never would have been able to go to Canada and the United States, where he met my mother and eventually became assistant concertmaster to the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra.

If none of that happened, I never would have been born and you would not be reading these words now.

Through his own resourcefulness and careful planning, my father was able to leave one of the worst places on earth and find a life of freedom in the West. I guess some of that must run in his family.

I supposedly had a Chinese great-grandfather who despite being illiterate, was able to walk into the nearest town and negotiate his way into becoming the wealthy manager of a construction company. The other great-grandfather was a chauffeur for the Japanese mayor of Shenyang during Japan’s occupation of Manchuria, secretly stealing fuel to sell on the black market while putting my grandmother and her sister through Japanese education which gave them a better lot in life. Other family members of my father’s generation became musicians to escape similarly difficult circumstances.

I can’t say that my own life has been anything close to as challenging, but I like to believe that my own mentality in seizing whatever opportunities I can find comes from what my father and his ancestors did. I’m reminded of that today on what would have been Dad’s 70th birthday, yet another one that we unfortunately can no longer spend together.

It’s approaching four years since my father passed away of colon cancer, and in many ways I probably still haven’t completely come to terms with it.

In September 2020, I traveled back to Pittsburgh from Kyoto to be with Dad after his illness suddenly worsened and we all thought the end was near. It was the height of the COVID-19 pandemic when international travel was anything but easy. The convoluted rules of border entry and restrictions on domestic transportation in Japan necessitated a roundabout route through Europe, which only increased the cost and time it would take to reach my family in the United States.

A lot of it is a blur to me. The amount of emotional weight I felt from both the imminent passing of my father and the overall dreariness of having to go through empty airports at redeye times in the middle of a global pandemic is an experience I would not wish on my worst enemies. But I dealt with it the same way I do with all trying situations: focus on the end goal and treat everything unpleasant along the way as necessary inconveniences.

I don’t have to be the first to tell you that the United States in 2020 was hardly a happy country. We talk about political and social polarization now, but I don’t think any of it holds a candle to how unhealthy of a country America was four years ago both metaphorically and literally. Yet there I was, visiting an unhealthy country to visit an unhealthy family member. It was hardly an auspicious homecoming, but I knew it was now or never to see my father while he was still conscious and able to speak.

Like millions of people who have witnessed family members slowly die of cancer, I too had to go through the motions of seeing someone once so healthy and full of life slowly wither away into nothingness. Of course, cancer is cruelest when it gives you a false sense of hope. There are days when the person is able to summon just enough energy to go outside for a walk or to eat a meal normally with everyone else. You almost, almost think that perhaps they have a shot at beating this. But then you are quickly reminded the following day that such hope is an illusion. They remain bedridden from morning to evening, and all you can do is make the dwindling remainder of their time as comfortable as possible.

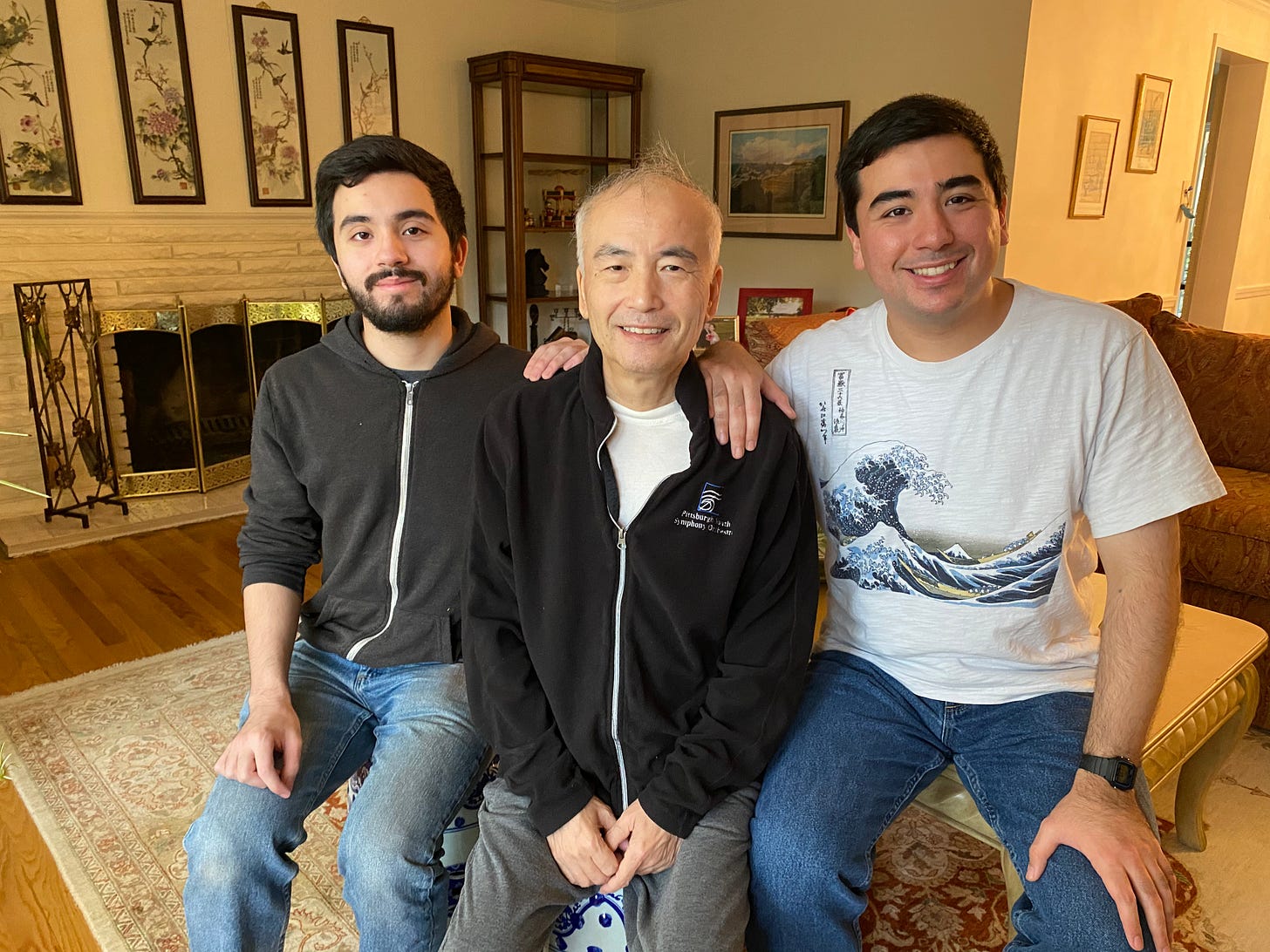

That was the routine I experienced in the roughly two months I spent with my father. Me and my brother did our best to help around the house with chores like trimming the hedges and picking up leaves. When we were kids, it was work we’d both dread doing, but at that point I think we just wanted something to do which could provide a sense of order and control. It may have been the emotional equivalent of rearranging chairs on the deck of the Titanic, but there was some meaning to it. After Dad passed away, the house would be sold. It was thus the last time I would ever step foot there and relive the moments of my childhood.

One of the most painful moments of my sojourn was being with my father and his relatives. I have an elderly aunt and uncle from China who have lived in Pittsburgh for over two decades, and they were also joined by my grandmother. Because I was there, we all decided to be together one final time before I would have to return to Japan. In typical Chinese tradition, best seen in the heartbreaking 2019 film The Farewell, they decided to not tell my grandmother about my father’s cancer until the very end.

Nai Nai was in her 90s and dealing with mental decline, but even she could understand what was happening. While I unfortunately never learned to speak Mandarin Chinese owing to my English-only upbringing, Japanese was the one language we could communicate in. For as long as I live, I will never forget the saddened look on her face as she told me that something was wrong with my father. I simply told her, “I know,” and left it at that. Further words were no longer necessary. She would go on to outlive my father by over a year, passing away at the age of 96 in 2022.

We all believed that Dad would pass away while I was there, but that did not happen. I had to make the painful decision to leave at the end of October because I was in the middle of my master’s program in Kyoto and applying to continue on to a PhD. I was already taking a considerable amount of time away, and missing the interview deadlines for the doctoral course was not an option. So we had to part when my father was still alive, and even now I often wonder if it was the right choice to make.

At the same time, we said goodbye when he was conscious and lucid enough to still speak like his old self. My family who had to take care of him until the very end had it much worse because they had to witness him lose the ability to eat, move, and eventually speak. He fought on through his 66th birthday in November until January 20, 2021, which was far longer than any of us ever thought. On his last day, I had to give my farewell over video call separated by a time zone 14 hours away. It was a devastating experience that I don’t think I can even properly put into words here, but what I saw of my father’s final diminished condition was a reminder that life truly is finite and that we are all on borrowed time. The one solace was that we had been sure to leave nothing unsaid before reaching this sad coda.

Before I returned to Japan, my brother and I recorded a few hours of conversations with Dad about his upbringing in Cultural Revolution-era China and his journey through life which eventually brought him to the United States. They were stories we had heard many times, but we wanted to preserve them for posterity. Those recordings exist in a Google Drive folder that I have not touched in over four years. Even now, I don’t feel mentally ready to reopen them and deal with the inevitable emotional heaviness they would create. Part of me hopes that they can form the basis for a future book project, but unfortunately my main connection to China died with my father.

I’ve often written about feeling like an eternal outsider throughout most of my life, but that holds especially true with the Chinese side of me. I have never been to China and I was never raised to speak Mandarin. There is no practical way for me to academically research the stories my father told me because I have no way of getting in touch with any of his surviving relatives in China nor would I be able to communicate with them even if I could. If I were to go to China I would feel like an utter foreigner and my history of publicly criticizing the CCP is not worth the risk, even if it’s probably low.

Hatred for the CCP though is something my father always carried with him. He naturalized as a U.S. citizen over a decade ago and truly embraced his newfound American identity toward the end of his life. Despite initially believing that China was on the right path of economic reform after the Cold War ended, Xi Jinping’s pivot to greater authoritarianism and actions toward Tibet, Xinjiang, Hong Kong, and Taiwan utterly sickened him. He would regularly tell me that he thought the current leadership was bringing China back to the Cultural Revolution he had escaped. Amusingly, he became more political as time went on and was more or less a Trump supporter because he believed that such an American leader would be the best way to punish the CCP as hard as possible.

I was wistful during the recent 2024 election, not necessarily because Trump had won, but because I was reminded of the conversations I used to have with my father shortly before he passed away. I can’t say that I completely agreed with everything he believed in, but Dad always thought deeply about political and historical issues despite having little formal education himself. In the end, he achieved the American Dream and constantly told me that the U.S. was the greatest country in the world. At the same time, he was always supportive of my choice to live in Japan, but would remind me to never forget where I came from.

I haven’t. Though I’ve previously written about why I’ve ultimately decided to live in Japan over the United States, I’m only here because of what my father achieved before me. The decisions he made are what allowed me to have the resources and circumstances to go to the other side of the world and get a start far better than most. While my life has been far easier overall, like Dad I was awarded a scholarship to study abroad and had to deal with the challenges of adapting to a different culture.

As a kid I would often make fun of Dad’s imperfect English and occasional lack of understanding of American culture, but now I’m finding myself in the same situation. Eventually I’ll have children who will speak far better Japanese than me because they will be raised completely in this culture. As Bane tells Batman in The Dark Knight Rises, “You merely adopted the dark. I was born in it, molded by it.” It’s a cycle that anyone who has planted their roots in another country will surely understand. I’m just carrying on that legacy.

As typical of most Chinese parents, Dad would always tell me to work hard, focus on studying, drink less, and exercise more. When I was younger I would often fail to understand why he was tougher on me than my mother was, but I now realize that it was always because he had my best interests in mind and wanted me to take advantage of the opportunities he never had. When he saw that I was doing alright for myself in Japan, I think he slowly realized that his work was done. He lived long enough to see me get accepted into my current doctoral program, which I was grateful for.

There are plenty of times when I wish Dad could still give me advice, and indeed the biggest tragedy is that he is no longer around to see my most important milestones. He didn’t live to see me complete my master’s, get married, or become a professional freelance journalist. He won’t be around to meet the children I hope to have one day with my wife or see where my academic career goes. At the same time, one of the last things he ever told me was, “I’m not worried about you.” That’s about the highest praise one could ever get from an Asian parent and I continue to keep in mind everything he imparted on me.

I also have decades of recordings from the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra to return to if I ever want Dad to be with me again in spirit. Look up any videos of the PSO uploaded to YouTube before the pandemic and chances are you’ll see my father sitting in third or fourth chair leading the first violin section. It’s the best preservation of someone’s memory one could ever have asked for. While I never continued on with the violin, readers of my weekly column Bonus Perspectives will also know that I regularly recommend classical music and aim to convey its artistic importance to readers. That lifelong appreciation for music a hundred percent comes from my father.

Besides being assistant concertmaster for the Pittsburgh Symphony, Dad taught violin lessons to dozens of students over the years. I occasionally get messages from his former pupils who all tell me the same thing: my father always pushed you to be better than you thought you could be. Some students became professional musicians, while others like me retired from playing the violin and went into something else. Either way, what he taught still applied to all walks of life. The only person who can prevent you from achieving your goals is yourself.

On what would have been my father Hong-Guang Jia’s 70th birthday, I look back on the time we were fortunate enough to spend together. It would have been ideal if he had stayed on for another decade or two, but it was a fulfilled life with no regrets. Tonight I will raise my wine glass in Dad’s honor and keep on living. It’s what he would have wanted me to do above all else.

Foreign Perspectives is a reader-supported Substack. If you like my work and have come this far as a new reader or free subscriber, consider opting for a paid subscription so I can continue writing in-depth articles such as these on a regular basis. Your support is greatly appreciated!

A beautiful tribute to my dearest friend. Thank you Oliver.

This is good and touching. Stories like your father's make me appreciate that America has a lot going for it, even now. (Repost, because I think it cut off my comment.)