Should You Live in Japan?

Coming to the Land of the Rising Sun isn't so hard, but staying with a fulfilling life and career are considerable challenges.

Foreign Perspectives is a mix of free and paid content. Certain articles such as these are exclusively for paid subscribers. If you enjoy the work I do, please consider upgrading to a monthly or yearly subscription. Your support is greatly appreciated and ensures that this Substack can continue to deliver high quality pieces.

With 37 million international tourists visiting Japan in 2024, it’s safe to say that this country is at the peak of its global popularity. A trip to Japan to millennials and Gen Z might as well be what a trip to Europe was for their parents; the kind of aspiration you should put on their bucket list because everyone seems to be doing it. Japanese soft power being stronger than ever is undoubtedly one of the biggest contributing factors to this phenomenon, and when you pair that with the weak yen, why wouldn’t you want to come to Japan?

Of course, going to Japan as a tourist is worlds apart from actually living in Japan as a long-term resident. There’s a saying I often hear which I’ve always thought was a rather banal observation: “I’d love to visit X country, but I could never live there.” This is a trite thing to say because it’s only stating the obvious. Tourists are typically shown the best bits of a country and given experiences specifically catered to them as temporary guests. Living anywhere different from what you’re typically familiar with is of course going to be a challenge. After all, the point of travel is largely for pleasure and escapism.

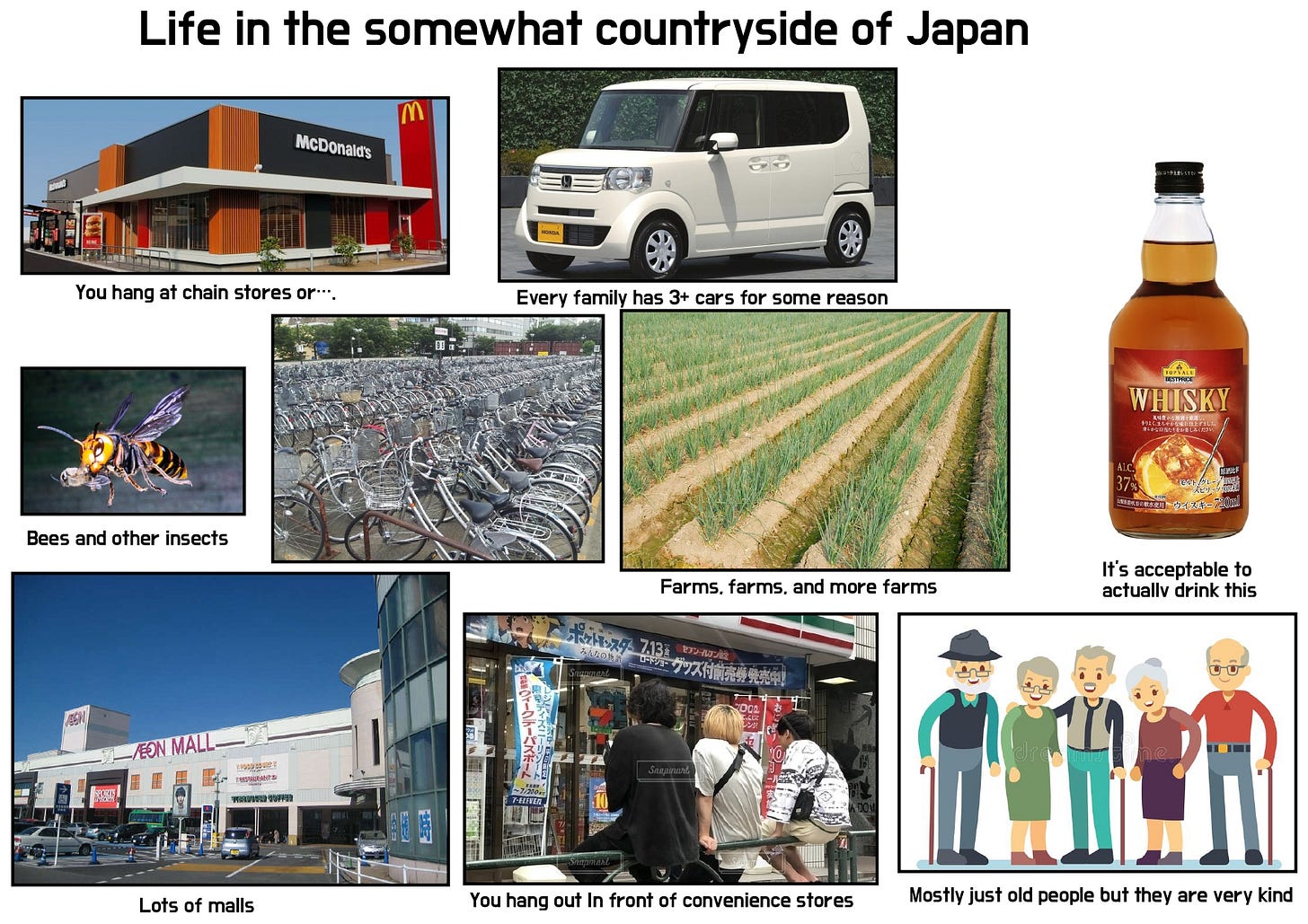

With that said, I do think the gap between tourists and residents in Japan has only grown larger in the last few years. Inbound travelers largely congregate in the big three cities — Tokyo, Osaka, and Kyoto — and don’t really see much else of the country. Those places of course can provide unique experiences, but most tourists are going to end up seeing and doing the same things on nearly identical itineraries. Social media has especially contributed to overtourism, turning previously special locations into over-congested nightmares. The average Japanese person dealing with rising costs of living and stagnant wages has no reason to go to these places.

So what’s it like to actually live in Japan when you leave the tourist traps? In 2023, I wrote a piece explaining why I chose to move here. In 2024, I discussed what foreign commentators often get wrong about Japan. This time around, I aim to provide an updated assessment on what the current state of things are in the Land of the Rising Sun. Is Japan an attractive place to make your home in 2025? Is the anti-foreigner sentiment real or imagined? And how exactly does one make a living here? Well, I’m still trying to figure out that last question myself as a grad student reaching the end of his PhD, but I’ll draw on the experiences of many others I’ve known.

In any case, here are some thoughts that have been on my mind lately.

Moving to Japan is relatively easy (if you know what you want)

The good news is that if you’re interested in moving to Japan, it’s arguably the easiest it’s ever been. We’re long over the days of the pandemic when prospective foreign visitors were barred from entering the country due to the travel ban, so if you simply want to step foot onto Japanese soil as a tourist, go ahead. Japan has visa-free travel agreements with 73 countries, so chances are high that this probably applies to you. Most of these allow a maximum stay of 90 days.

However, don’t forget this crucial point: you *cannot* work in Japan while on a tourist visa. That should go without saying, but many with the time and cash to burn in this country for an extended period of time are sometimes under the mistaken impression that they can come here as a tourist and simply find work afterward. It doesn’t work that way and you’re most likely going to set yourself up for some legal trouble if you attempt it. You can certainly look for jobs and gauge what places are hiring while you visit on holiday, but the process of securing a work visa will almost assuredly require you to return to your home country.

I highly recommend at least visiting Japan before deciding to move here. A short holiday will obviously only give you a very skewed perspective, but it’s better than going in completely blind. You can gain some insights into how things are done and if the pace of life in the bigger cities is something you might be able to adapt to. Try to take the time to go off the beaten path as well and visit locations most tourists tend to be unaware of.1

The easiest time to attempt life in this country is when you’re young and still trying to figure things out. I first arrived in Japan when I was 19 thanks to an internship and study abroad program offered by my university which lasted a collective total of 15 months, so I strongly recommend seeking out those kinds of opportunities if you’re around that age. Trust me, there’s no better feeling than being in your early 20s while living abroad in a foreign country. After that though, it gets more complicated the older you get.

I returned to Japan via a scholarship for master’s in international relations provided by Japan’s Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology or MEXT. It was a very generous stipend, but unfortunately the Japanese government may be looking toward ending such programs over the next few years. That’s a topic for another day, but if you were planning on coming to Japan via the scholarship and higher education route, I suggest you start doing your research now. Most of these funding opportunities accept candidates up to the age of 35.

Beyond that, many choose the English teaching path like the JET program to get their foot in the door, but as I’ll explain in the next section, you shouldn’t bet on this being a sustainable, permanent gig. Instead, the best piece of advice I can give is to ask yourself what you would like to do in life regardless if you were living in Japan or not. One viable option is looking for employment at a company within your own country that could lead to work in Japan down the road. Start learning Japanese, build your portfolio, and have the marketable skills that make you an attractive candidate for being stationed in Japan.

The language bit in particular is non-negotiable if you want to have a successful life here.2 With Japan’s declining population, the government is currently looking for “specified skilled workers” to fill important jobs in fields like construction, aviation, and agriculture. This is not the route I personally chose, but there are no shortage of open occupations in Japan. This is why I believe it’s “relatively easy” to move to Japan now. If you already have the qualifications and a solid plan for the industry you want to get into, knowing Japanese on top of that should practically make you a shoe-in for a work visa.

It’s still certainly possible to move to Japan in your late 30s and 40s, but by that point you have to consider any existing responsibilities and commitments in your own country. Are you married? Do you have kids? Does it makes sense to change your career? The more of these things tying you down, the less likely moving to Japan long-term becomes. If you’re already doing pretty well and you have the disposable income, it might make more sense to instead look toward staying in Japan for only a couple of months on an annual basis. As long as you don’t overstay your tourist visa, there’s nothing preventing you from taking a yearly holiday here.

Staying in Japan is hard (and English teaching probably isn’t a career)

Getting a work visa to come to Japan is the initial hurdle, but it’s arguably the easiest part. What comes next is deciding how long you will stay in Japan and the steps required if you want to make it your permanent home. Foreigners have risen to around 3.8 million people or roughly 3% of Japan’s population — a considerable increase from the numbers seen over 20 years ago. With that said, this data needs to be viewed within the proper context.

Of those foreigners, less than 919,000 are classified as permanent residents. The rest fall into categories like temporary trainees and students who will stay in Japan for a few years, but will return to their home countries. Reasons for leaving are numerous, but they mostly come down to hitting a career ceiling and being unable to fully adjust to the culture. It should come as no surprise that the vast majority of immigrants to Japan come from neighboring countries. Most domestic discussions around “gaikokujin” are pretty much referring to the thousands of Chinese, Vietnamese, and other Asian workers, not the far smaller number of Westerners who happen to come here.

What does this mean? Well for starters, it’s generally easier for other Asians to adapt to another Asian culture. The number of people from Anglosphere countries has also increased, but they tend to be short-term expats who ultimately leave after being unable to fully integrate. The longer you stay in Japan, the more you have to become accustomed to how things are done here. As I’ve often emphasized, learning the language is just the first barrier. You also need to gain cultural fluency in understanding social cues, nuances, and general societal rules that can seem downright arbitrary and pointless. All of that can take years to understand just on a base level, so seriously reconsider coming to Japan if you aren’t ready to commit.

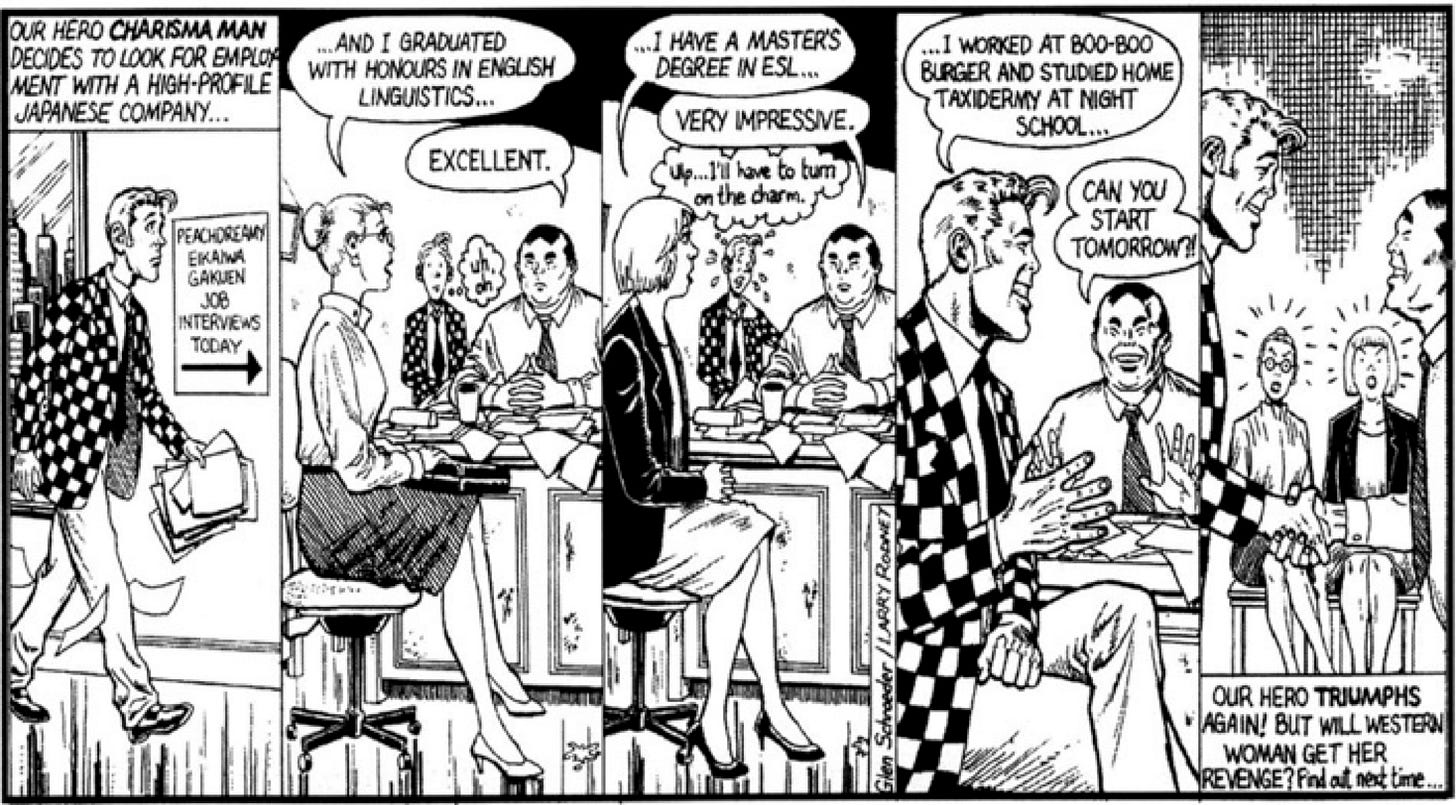

So what if you’re able to get over those cultural differences and you’re doing a decent job gradually picking up the language? You then have to consider what your future is going to be in Japan beyond whatever entry level position got you here. Expat life on convenience store food in a one bedroom apartment is fine in your early to mid 20s, but that can’t last forever. The majority of Anglosphere expats start in Japan on English teaching because most of those jobs only require a BA and a pulse. I cannot emphasize this point enough: get out of this field as soon as you can into something else.

This subject too is worthy of its own article, but I’ll give you the abridged version here. English teaching in Japan, apart from qualified instructors employed at places like universities, is a career dead end. For Assistant Language Teachers (ALTs), wages have stayed stagnant between ¥230,000 to ¥300,000 per month for years. With how weak the yen is, that’s roughly $1500 USD to $2000 USD a month. That’s barely enough to get by on in rural areas, while you would be in a state of near-poverty in major cities like Tokyo. Some places offer better wages than others and you might get subsidized housing if you’re lucky, but there’s a finite ceiling to how much you can make. Forget about having any kind of savings on what’s essentially a fast food worker’s salary.