When Theodore Roosevelt Almost Died in the Jungles of Brazil

The overlooked story of how the former U.S. president surveyed the River of Doubt with Colonel Cândido Rondon and the events which led up to it.

After finishing their time in the White House, it’s common for most U.S. presidents to keep out of the public eye and largely stay quiet. Whether they were successful in office or not, the presidency is one of the most difficult and stressful jobs in the world. It makes sense why the majority would choose to rest on their laurels and enjoy their twilight years in relaxation.

But then again, most presidents are not Theodore Roosevelt.

Having served from 1901 to 1909 as the 26th president of the United States, T.R., as he would often go by, ranks among one of the greatest and most beloved leaders in American history. He was also the youngest, having entered the White House at the age of 42 following the untimely assassination of President William McKinley at the hands of an anarchist.

In domestic affairs, Roosevelt was a progressive who made himself the enemy of big business and cigar-chomping bankers like J.P. Morgan, advocating that monopolies should be broken up via anti-trust laws, that the average American deserved fair wages, and that the federal government should take a greater role in regulating the economy. This also extended to Roosevelt’s passion for nature and conservationism, which he would maintain his entire life.

When it came to foreign policy, T.R. famously stated his view that one should “speak softly and carry a big stick,” which set the gears in motion for America’s greater influence on the world stage. For better or worse, he also strongly believed in the U.S. needing to play the role of global policeman lest European or other foreign powers seize upon this power vacuum. He was an admirer of Japan, but a skeptic of Russia and Germany.

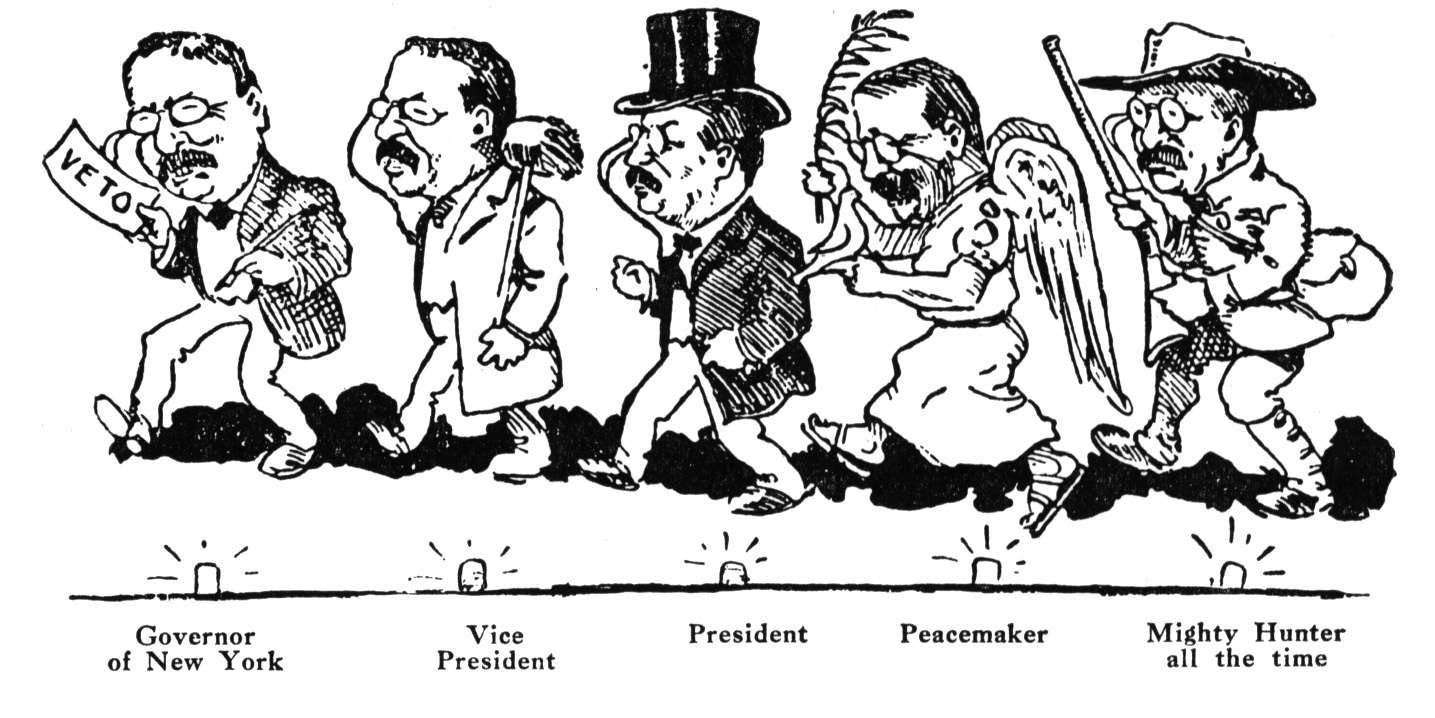

Roosevelt attempted to run for a third term as president in 1912, even going as far to create his own political party after failing to win the Republican nomination, but was unsuccessful. It was a bitter blow for the man who did not take defeat lightly, and he did not want to spend his post-political years in irrelevance or obscurity. Roosevelt thus eagerly seized the opportunity for a new challenge that offered the chance to explore an uncharted river in the jungles of the Amazon.

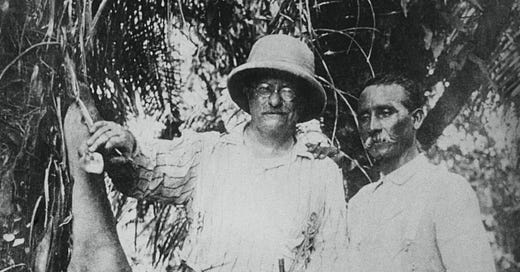

Joined with his son Kermit, Brazilian explorer Colonel Cândido Rondon, and naturalist George Kruck Cherrie, it was a perilous expedition that would greatly change T.R.’s outlook on life, while nearly ending it altogether. But despite the historical significance of the journey for both Roosevelt and Rondon’s countries at the time, most Americans and Brazilians have long forgotten it.

This is the story of Theodore Roosevelt and the River of Doubt.

The Strenuous Life

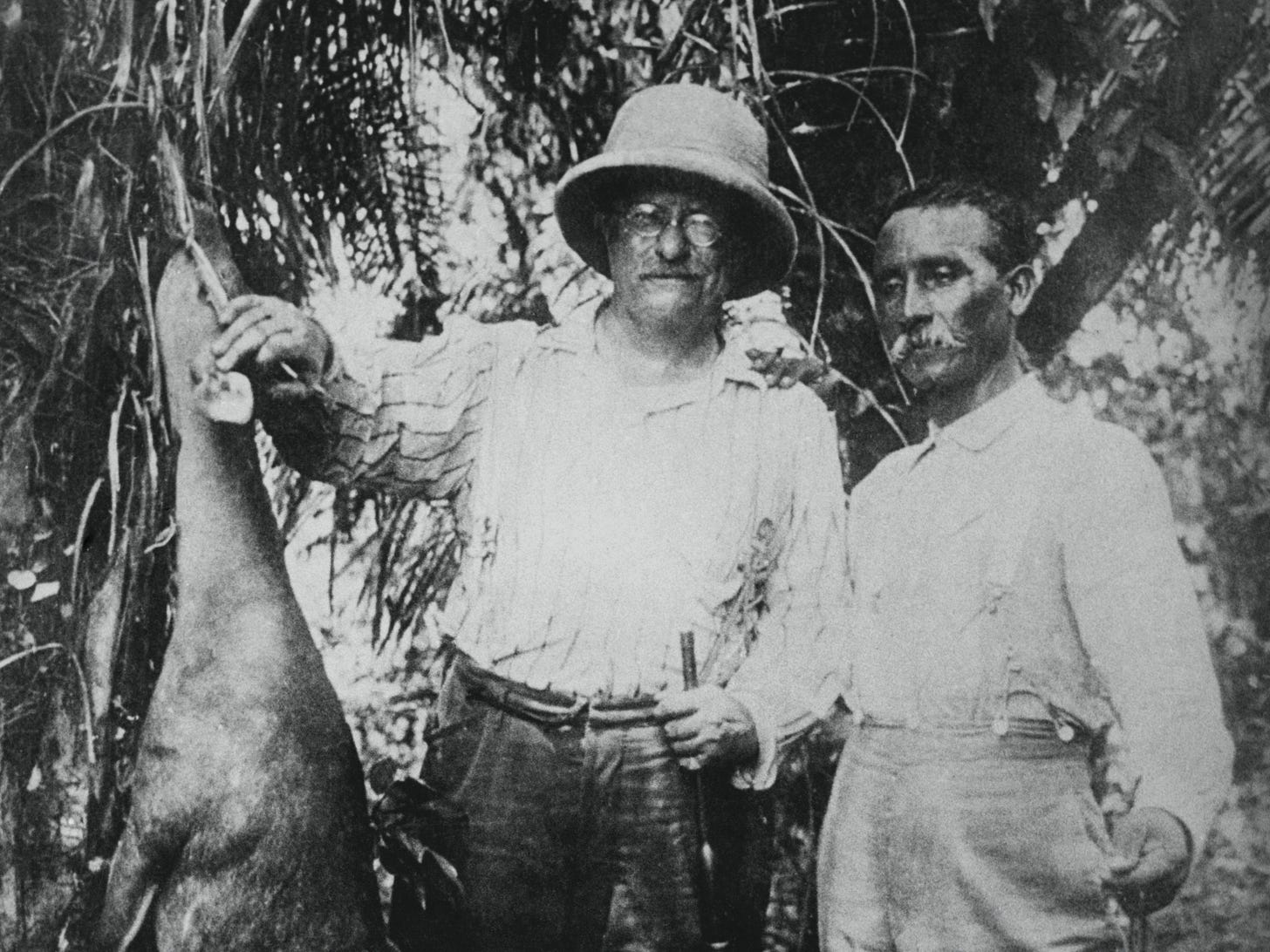

Though born into a wealthy New York City-based family on October 27, 1858, Theodore Roosevelt’s early years were marked by ill-health and tragedy.

As a boy, Roosevelt suffered from a weak constitution due to his asthma. He was picked on by older and bigger children, but boxing lessons and an exercise regiment encouraged by his father lead to improved health over time.

T.R. additionally displayed an early affinity for animals, insects, and natural landscapes, while a childhood encounter with a dead seal in a market was particularly impactful. Overcoming his health issues and establishing an interest in all things related to nature would be two of the biggest factors that inspired Roosevelt to venture into Brazil many decades later.

Having embraced the importance of both physical and mental exercise, Roosevelt seemed to be destined for great things after graduating from Harvard University and Columbia Law School. He shifted his career focus to politics and was successfully elected as a member of the New York State Assembly in 1882 at the young age of 23. And if that wasn’t enough, he also published his first book the same year on the War of 1812 due to his dissatisfaction with existing texts around the subject.

Yet Roosevelt’s grand successes went up against his grand losses. He had married socialite Alice Hathaway Lee in 1880, only for her to meet a tragic end on February 14, 1884 when she passed away at the age of 22 from Bright’s disease. T.R.’s mother, Martha Bulloch Roosevelt, had died the same morning of typhoid fever. In his journal, the grief-stricken young man famously marked the date with a black “X” and wrote “The light has gone out of my life.”

Roosevelt’s first child, Alice, had been born just two days before her mother’s death. Her existence was a haunting specter of the woman he had lost, and her name alone brought up painful memories. The tumultuous life of the girl who would grow up to be Alice Roosevelt Longworth is worthy enough for its own article, but she was just one of the many children T.R. would go on to have.

Taking a sabbatical from politics while dealing with his grief, Roosevelt spent two years on a cattle ranch in the Dakota Territory, which further contributed to his toughened personality and passion for conservationism. He would remarry in 1886 to his childhood friend Edith Kermit Carow and go on to have five children. This also coincided with his re-entry into politics which spanned from being elected as commissioner of the now-defunct United States Civil Service Commission in 1889 all the way up to governor of New York in 1899.

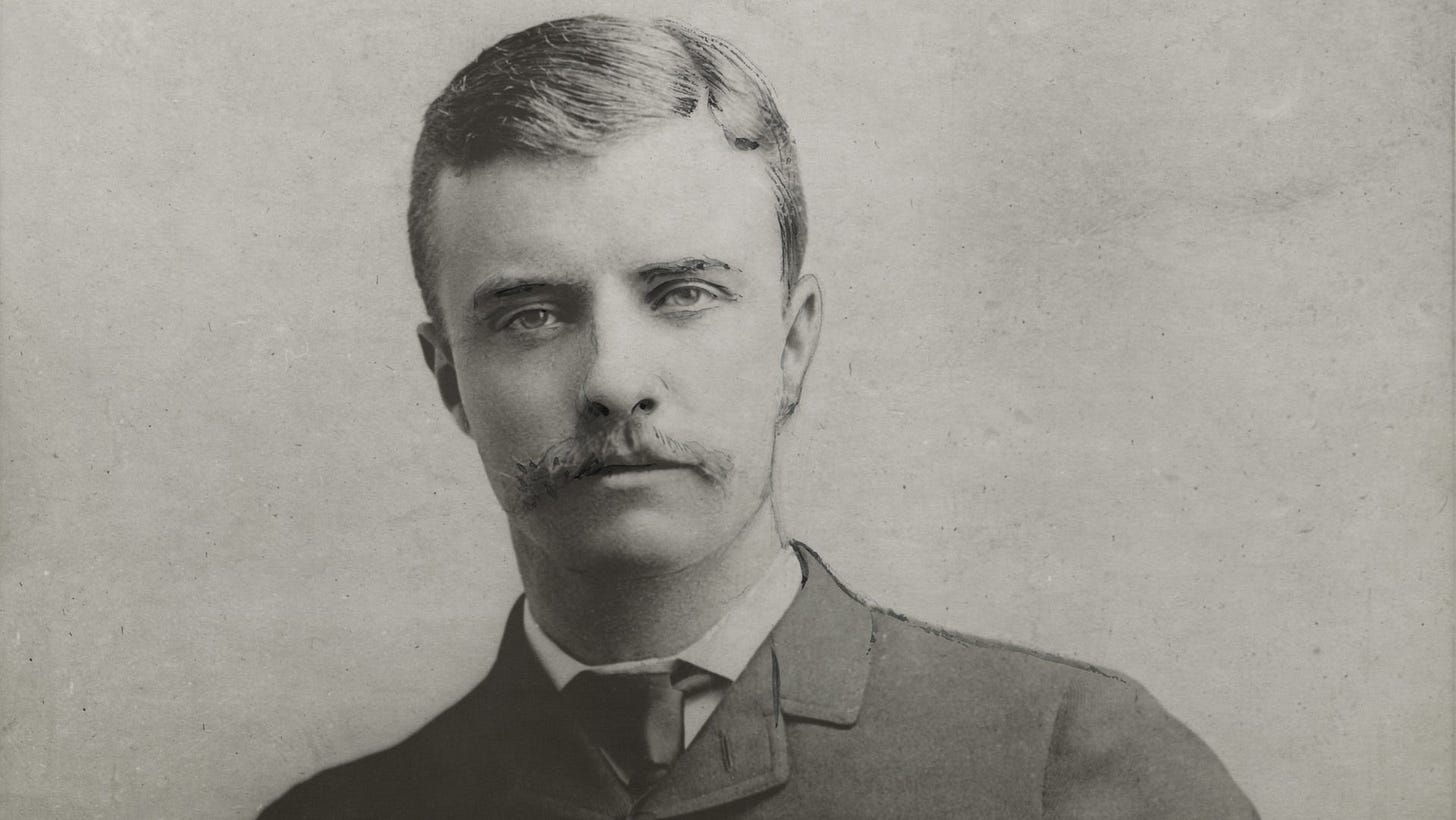

During this decade, Roosevelt rose to public prominence as assistant secretary of the navy under the William McKinley administration in 1897. He resigned the following year to organize and lead the Rough Riders during the Spanish-American War. The exploits of this volunteer regiment in Cuba became highly publicized throughout the United States, with Roosevelt being praised as a national hero particularly for the unit’s actions during the Battle of San Juan Hill, though the mythology around the Riders tends to be somewhat overplayed.

All of this context is necessary to establish just what kind of person Theodore Roosevelt was before he even became president of the United States. Him assuming the role of both vice president and president was the result of his predecessors dying unexpectedly in office, leading many in the press to dismiss the 42-year-old politician as an “accidental” leader. But Roosevelt refused to leave what happened in his life up to chance or fate, believing strongly in an individual’s free will to choose his own path.

This was reflected in his 1899 speech entitled “The Strenuous Life,” which Roosevelt delivered to a Chicago audience when he was governor of New York.

“We do not admire the man of timid peace. We admire the man who embodies victorious effort; the man who never wrongs his neighbor, who is prompt to help a friend, but who has those virile qualities necessary to win in the stern strife of actual life. It is hard to fail, but it is worse never to have tried to succeed. In this life we get nothing save by effort.”

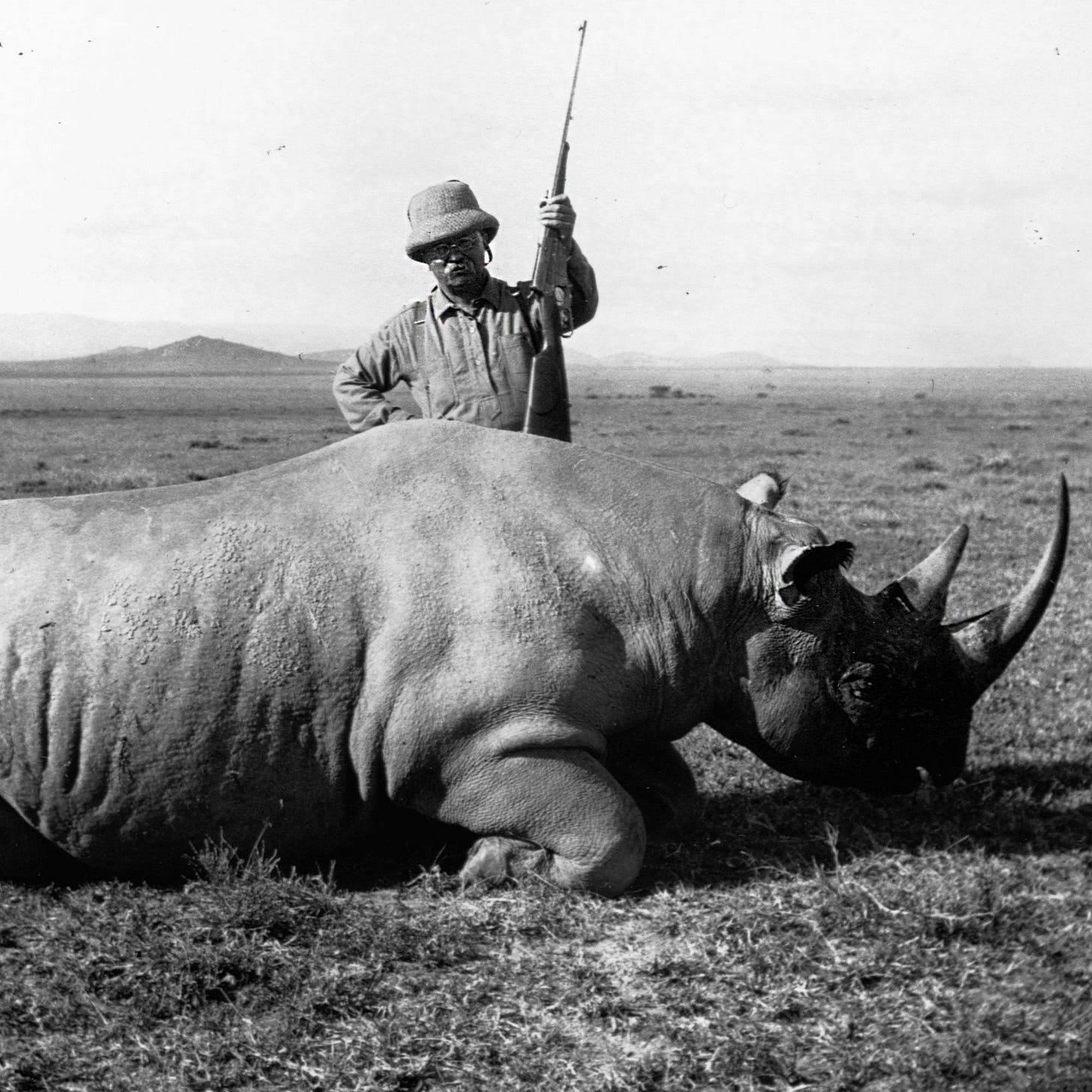

Much has been written about the highs and lows of Roosevelt’s presidency, but it was merely one part of the adventurous life he lead in retrospect. As soon as he left office in 1909, T.R. embarked on a 10-month safari tour of Africa to collect specimens for the Smithsonian Institution. Together with his son Kermit, the Roosevelts hunted 512 large animals including lions, elephants, and rhinoceros, while also killing or trapping thousands of other smaller game such as birds and reptiles.

While some today may view the amount of dead animals as excessive, Roosevelt didn’t consider hunting to be a contradiction of his conservationist ideals, instead believing that the British government’s efforts to set up game reserves in their colonial possessions throughout Africa actually helped to preserve fauna. The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles, a spin-off television series from the film franchise which I have previously written extensively about, even featured an episode where Indy meets Theodore Roosevelt during this 1909 expedition.

T.R.’s Africa adventure brought him additional fame and glory, but it was also more or less a trial run for the far more dangerous expedition to Brazil he would undertake just a few years later.

The Gandhi of Brazil

The other half of this story comes with Cândido Rondon, a name unfamiliar to Americans, but a national hero in his native country of Brazil.

Born as Cândido Mariano da Silva in Mato Grosso on May 5, 1865, the future colonel’s early upbringing could not have been more different than Roosevelt’s. His father died of smallpox before he was even born, while his mother passed away when Rondon was only two years old of the same ailment. He took his surname from the uncle who raised him and faced a life of great poverty which severely limited his future prospects.

Rondon’s birth came just when the Empire of Brazil, Uruguay, and Argentina were locked in a bloody conflict with Paraguay known as the War of the Triple Alliance. Death, disease, and famine were early hallmarks of his childhood, but against all odds, Rondon survived. He moved to Rio de Janeiro at the age of 16, which would have been a stark change from the remote jungle towns he had grown up with. The only pathway to a better life for the teenager was Brazil’s military.

Rondon found himself as an outcast like young Roosevelt, but with circumstances that were far worse. The poverty he had come from left him constantly malnourished and weaker than his peers, while his rural background additionally ostracized him. But Rondon was an extremely dedicated student, waking up at 4 a.m. every morning to swim in the sea and studying for hours to earn a bachelor’s degree in mathematics and science. He achieved the rank of military engineer which allowed for unprecedented stability he had never experienced before.

Born of mixed European and Brazilian Indian descent, Rondon was an early advocate for the rights of his country’s indigenous people and ethnic minorities. Brazil abolished slavery in 1888, being the last country in the Americas to do so. Like the United States, it faced a plethora of questions around how to deal with its various Indian tribes. Rondon strove to “bring civilization” to the indigenous residents of Mato Grosso, and this would be the dominant goal of his entire life and career. His push for social change eventually caused international observers to dub him as the “Gandhi of Brazil” later in life.

Much of this came from Rondon’s belief in Positivism, a philosophical school of thought developed by Auguste Comte which emphasized the scientific method and rational thought. Positivists only accepted what could be directly experienced through sensory experiences as true, while they rejected concepts such as mysticism and religious faith. On a social level, this drove Rondon to believe that societal progress was inevitable and that Brazil’s indigenous people needed to be properly integrated, or they would be left behind.

Rondon aimed to establish direct contact with the country’s most isolated tribes, and the opportunity arose in 1890 when he was tasked with leading a commission that planned to build a sprawling telegraph line across the interior of Brazil. Being assigned to the Rondon Commission became infamous as a perilous task often reserved for lazy or violent soldiers, while many died throughout the dangerous voyages in the uncharted jungle territory. Tropical diseases like malaria could incapacitate or kill even the strongest of men if a hostile Indian tribe did not end their lives first.

Regardless of the hardships he faced, Rondon was resolute in achieving his mission. His men were skeptical and sometimes even dumbfounded at his civil approach to unfriendly tribes, but this tactic lead to tangible successes in brokering peace with most of them. Despite being a military colonel, Rondon was an avowed pacifist and aimed to avoid conflict when possible. His efforts paid off when his commission finished building the telegraph line in 1895. Rondon married and had seven children around this time, but his demanding role of bringing Brazil into the 20th century meant that he was rarely home to enjoy a typical domestic life.

“My Last Chance to Be a Boy”

Earlier in 1913, Theodore Roosevelt found himself at a crossroads of what direction he should take his life following his failure to secure a third term as president. He had received an invitation from an Argentinian history museum to give a guest lecture, with the venue offering a handsome sum for his presence and complete freedom to dictate all the terms of his visit.

Roosevelt needed the money, but he also wanted to see his 23-year-old son, Kermit, who was at this time an expatriate worker building bridges in South America. The two had bonded during their African adventure, and Theodore was pleased that Kermit had continued to test his mettle by seeking fortune and glory in a remote continent that most Americans still knew very little about.

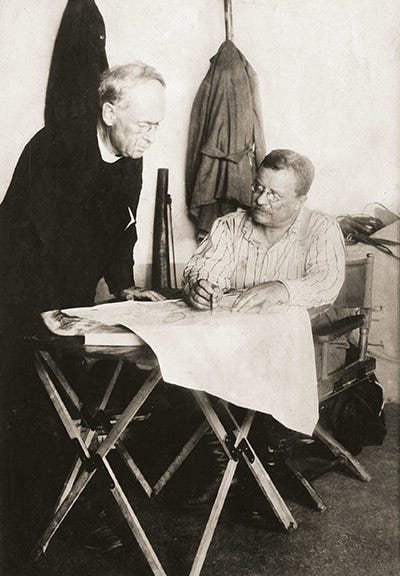

Beyond just the speaking tour through Brazil, Uruguay, and Argentina, T.R. consulted with the American Museum of Natural History to see if he could make some scientific achievement that would be of benefit to his countrymen. He was close friends with Catholic priest Father John Augustine Zahm, who had always urged him for years to take a trip to South America. Zahm was a devoutly religious man, but also an early proponent of Darwin’s theory of evolution and shared the same passion for naturalism as Roosevelt.

Zahm initially pitched what was essentially a greatest hits itinerary across South America’s best-known rivers, but the former president soon realized that a trip which any ordinary man could accomplish was not enough to satiate his desire for something exciting and new. After Roosevelt’s party arrived in Brazil in October, the country’s foreign minister proposed an alternative suggestion — a trek down an uncharted river.

The Rio da Dúvida, or River of Doubt, was the kind of mystery that proved to be irresistible for Roosevelt. Colonel Cândido Rondon was the one who had discovered its source during an expedition five years previously, but other than that, the river was a complete enigma. No one had any idea how long it was or what territory it went through. The idea of such a dangerous journey through the hazards of Brazil’s thick jungles would scare even seasoned explorers, but Roosevelt was undeterred.

T.R.’s sponsors back in the United States were horrified that the aging 55-year-old was planning on doing something so risky, but he described it as his “last chance to be a boy.” Not only was Roosevelt getting on in years, but him surviving both an assassination attempt in 1912 and a serious carriage accident over a decade previously had caused doctors to urge him to take his health more seriously. His wife Edith, who had accompanied him to Brazil, was also opposed to the expedition. She only relented after convincing Kermit to join the explorers, a task which the younger Roosevelt only did so reluctantly.

Talented in foreign languages, Kermit’s years spent in Brazil allowed him to gain fluency in Portuguese, as well as familiarity with the country’s people and culture. He was engaged to American socialite Belle Willard and madly in love with her, but at the same time did not want to abandon his father when it was clear that his skills were needed. He looked back fondly on their time in Africa and knew that this would be their last opportunity for one final adventure.

Journey Into the Unknown

The factors of history occasionally align to result in faithful meetings between titanic individuals, and that proved to be the case when Colonel Cândido Rondon greeted former U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt on December 12, 1913, having agreed to be the co-leader of the expedition after receiving official orders from the Brazilian government.

The two men did not speak each other’s language and could only communicate in rudimentary French or rely on Kermit as an interpreter. Despite the language barrier, however, Roosevelt knew that he was in the presence of an esteemed military official after learning about Rondon’s background. Both would form a close friendship as they voyaged to answer one of the last unsolved mysteries of the South American continent.

The expedition was plagued with problems from the outset. Father Zahm had ordered large motorboats for the trip, but was informed by Rondon that they would not be suitable for the twisting river and dense jungle foliage. Explorer Anthony Fiala was originally designated as quartermaster for the journey, but he was hardly the right man for the job. The man had been part of not one, but two failed expeditions to the North Pole and the tropical landscapes of Brazil jungle could not have been more different.

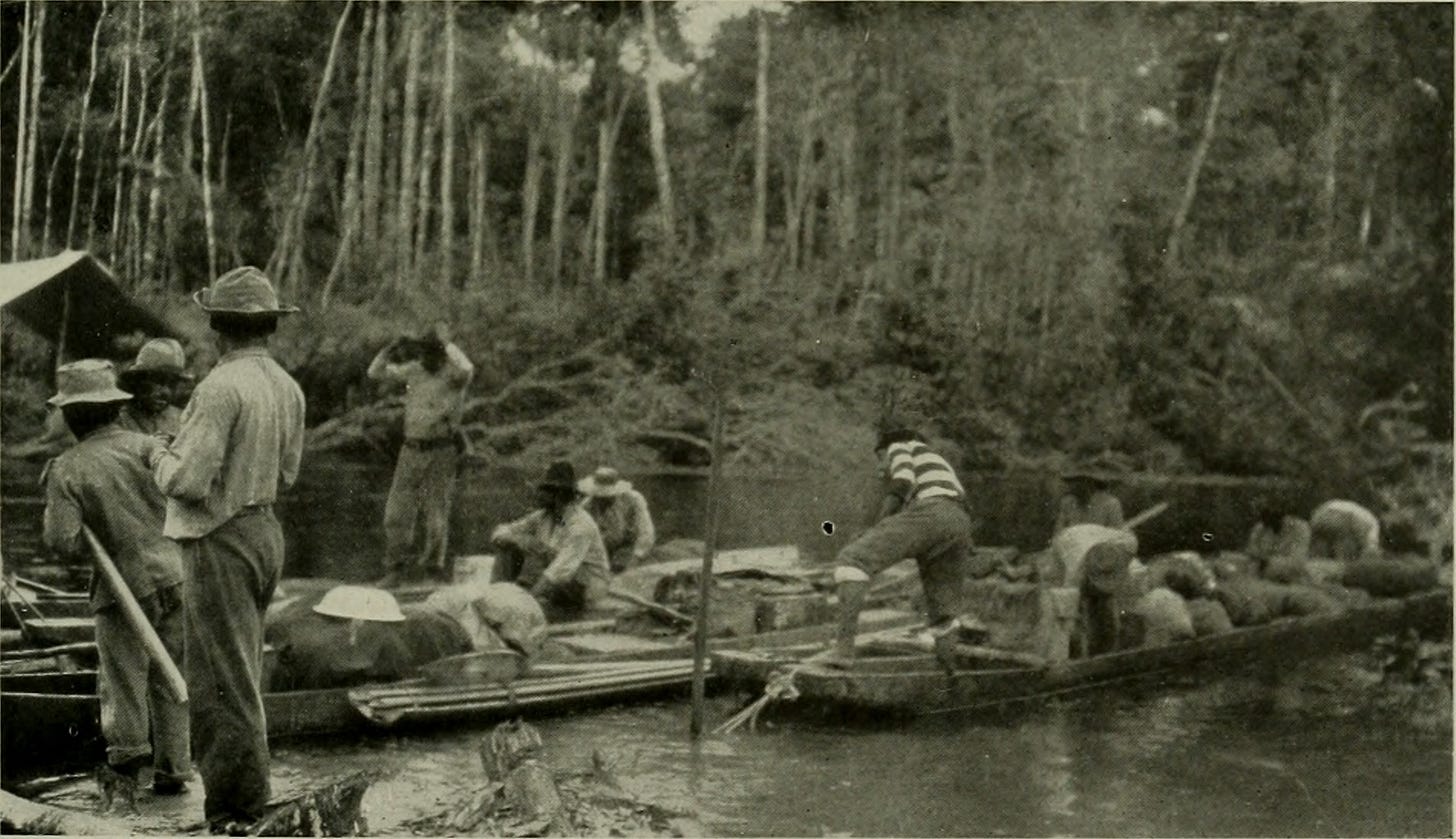

But both Roosevelts quickly showed Rondon that they could hold their own. Before setting off on the expedition proper, the party spent late 1913 in a riverside town where T.R. demonstrated his survival skills on multiple jaguar hunts which left the accompanying Brazilian officers and camaradas (laborers) more exhausted than he was. Yet another setback occurred around the question of how to deal with the 360 large boxes of supplies and rations which would be needed throughout the trip. Nearly 200 pack animals pushed forward in two separate detachments, one lead by Roosevelt and Rondon, the other lead by Rondon’s trusted confident Captain Amilcar Botelho de Magalhães.

As the party progressed, it became clear that serious planning around food was necessary. Rondon ordered that the men would eat only twice a day, the first meal early in the morning between 6 and 8 a.m., while the second would not occur until later in the evening. It was tough having to go without nourishment for most of the day, but it was the only way to guarantee that the provisions would last. While the 220-pound Roosevelt was used to hearty meals, he did not wish for special treatment and abided by the rules.

But one source of tension was both sides’ differing views of race. Father Zahm in no uncertain terms expressed his displeasure in having to sit next to a black driver and had previously written that the United States was not ready for the mixing of races seen in Brazilian society. He viewed secular ideologies like Rondon’s Positivist beliefs as heretical and dangerous, which was one motivator in the priest attempting to baptize as many individuals as he could throughout the trip. The Brazilian colonel, however, was a staunch opponent of racism due to both his own mixed ancestry and work with indigenous people. He had learned multiple tribal languages throughout his travels and would have preferred himself to die than for his men to kill a single Indian.

Being a known advocate of eugenics like many American progressives of his day, Roosevelt’s attitudes also differed considerably from Rondon. Owing to his ranching experiences in the Dakota Territories, he had famously said “I don’t go so far as to think that the only good Indians are the dead Indians, but I believe nine out of every 10 are.” Upon becoming president, his views around race somewhat mellowed and he took some tangible steps to improve civil rights, such appointing an African-American woman named Minnie Cox as postmaster. But while he acknowledged the mistreatment of Native Americans, him being ahead of his time in promoting conservationism ironically had the negative effect of stripping countless tribes of their ancestral territories.

Still, the expedition to Brazil undoubtedly changed Roosevelt’s outlook on race for the better. He saw firsthand how hard Rondon’s team of camaradas worked throughout the voyage and while he did not always agree with the colonel’s pacifist views toward indigenous tribes, he was impressed with the progress he had made. Given all the dangers they faced along the way from perilous terrain to deadly jungle diseases, Roosevelt knew that the group would have to work together regardless of whatever ideological differences they had.

Roosevelt’s right-hand man Frank Harper contracted malaria and decided to return home. Kermit too also came down with the infection, but he was used to regular bouts of it having lived in Brazil for so long. While T.R.’s son was young and relatively healthy enough to keep going, this was not the case for everyone. In order to guarantee that the expedition would reach its goal, cuts had to be made.

Famed naturalist George Kruck Cherrie was with them and stayed because of his expertise, but English explorer George Miller Dyott was out and instead tasked with descending the Rio Gy-Paraná, a much less dangerous (and less important) river. Father Zahm too would also be leaving, Roosevelt having concluded that his old friend was not physically capable of going down the River of Doubt with them. By early February, he would dismiss Anthony Fiala, concluding that his experience in the Arctic had not translated to the jungle.

The party of now 22 men continued on, but the most trying events were yet to come.

Brush With Death

Navigating through the River of Doubt was particularly a challenge because of how much it twisted, turned, and coiled through the Brazilian wilderness like a snake. Rondon correctly estimated that it poured into the Madeira, the source of the Amazon River, and based his direction on that conjecture. But at 470 miles (760 kilometers) long, the party had a considerable trek ahead of them once the reached the start of the river. Even worse, they had no boats.

Rondon deemed the motorboats Roosevelt’s team initially brought with them as too heavy to take through the jungle and useless for navigating the river. He instead purchased seven dugout canoes from Nhambiquara Indians, but their poor construction instilled little confidence. Even among other tribes, the Nhambiquara were regarded as being primitive with their tools and technology. Being hundreds of miles away from civilization, the group had no other option but to use the aging and cumbersome vessels despite the high risks.

The land the River of Doubt passed through was additionally full of dangerous animals from the largest jaguar to the smallest poisonous frog only a few centimeters long. Roosevelt himself was even bitten by a coral snake, but the thick leather boots he was wearing prevented the deadly venom from entering his system. The ex-president though was not bothered by the danger, rather he reveled in being up close to so much unfamiliar flora and fauna. He constantly had pen and paper in hand to chronicle the entire expedition, writings which publications back home were willing to pay top dollar for.

Rondon, on the other hand, was under pressure from his government to provide an accurate survey of the river and fill in the many gaps left behind by previous explorers. Kermit assisted him in placing the sighting rod used to make precise measurements, but the work was long, tedious, and slowed the party down. Since he was at the front, this placed Roosevelt’s son at the highest risk of meeting his end via an unseen whirlpool or Indian arrow.

Battling through rapids, dwindling rations, and other threats to their lives as the men continued their descent, a turning point to the expedition came on March 15, 1914. Early in the morning, Rondon spotted what he considered to be a spot of the river too dangerous to navigate and ordered his men to pull over until the rapids subsided. Kermit, however, decided to risk it anyways and paddled forward with two camaradas João and Simplicio in tow. But just as the colonel had predicted, the river’s current proved to be too strong and the tiny dugout capsized with the three men in it. Kermit and João miraculously survived the ordeal. Simplicio did not.

Seeing his son nearly drown caused Roosevelt to seriously regret bringing Kermit on the expedition, and he vowed to protect him for the rest of its duration. In his journal, Kermit appeared to show little sign of any outward guilt for indirectly causing Simplicio’s death or any desire to be less reckless despite his blunder. It appeared that he had inherited much of the same stubbornness and stoicism from his father. Rondon, although angry that Kermit had disobeyed his orders, did not blame him for what happened and everyone who accompanied the colonel on his expeditions knew that the risks of death would be high.

Rondon named the waterfall that ended Simplicio’s life after the deceased camarada, erected a short inscription on the camp marker they would leave behind, and promised that his family would receive any money earned from the expedition. There was little time to grieve as the trip had to go on. The men were on a near-starvation diet as their supplies ran low, and the Americans were baffled to see such little game they could hunt for food.

Heart of Darkness

The flora and fauna of the Amazon rainforest had developed evolutionary strategies to avoid being easily captured or eaten. Even fruits, nuts, and seeds were difficult to find, as the plants which produced them had adapted to ensure that their offspring would be well-hidden from predators. Fewer seeds meant fewer birds and smaller mammals, which in turn meant fewer bigger game that would eat them. Only a patient expert with extensive knowledge of Brazilian wildlife would know what to look for and properly stalk prey, but time was a luxury the expedition didn’t have.

Still, not all hope was lost. Rondon’s men were successfully able to capture large fish for the group to sustain on only a couple of days after the Simplicio incident, which meant that they wouldn’t go hungry. Soon afterwards, they also found an undiscovered tributary which Rondon decided to officially name as the Rio Kermit. He went on to announce that the River of Doubt would be officially named the Rio Roosevelt in honor of the former U.S. president. The river still bears his name to this very day over a hundred years later.

While great progress had been made in navigating the river, danger still lurked behind the veil. Rondon realized that they were being hunted by a tribe of Indians unknown even to him. They turned out to be the Cinta Larga, a group so isolated that Roosevelt and his men were likely the first white people they had ever seen. The Cinta Larga were experts in jungle warfare and surviving in the most desolate conditions. They were also infamously known to be cannibals that devoured the flesh of their conquered enemies. While they often went to war with other tribes, this would only be done following group majority consensus.

The Cinta Larga had not yet attacked the expedition, but tensions grew between Rondon and Roosevelt on what should be done. Rondon, owing to his lifelong commitment to establishing peaceful relations with indigenous tribes, was adamant that they remain calm and attempt to befriend them. Roosevelt, however, was far more impatient and wanted to reach the end of the river as soon as possible. They further clashed on Rondon’s insistence of conducting a detailed topographical survey, which Roosevelt believed slowed the expedition down and endangered his son.

With great reluctance, Rondon relented and agreed to do an abridged version of the survey he initially wished to do. Despite their disagreements, Roosevelt continued to pull his weight throughout the entire expedition. Him being a former U.S. president had little bearing on his duties, such as washing clothes or assisting with hunting. George Kruck Cherrie spoke glowingly of him, writing that there was “no camp duty that the Colonel shirked,” and that Roosevelt “stood ready and willing to do his share.”

Despite having been in relatively good health for his age amid the trying conditions around him, not even Roosevelt could escape the disease of the jungle. By late March, he had come down with a fever which robbed him of his strength and accidentally cut his right leg on a sharp rock. While this would have been an easily treatable injury back home, even the smallest cut could prove to be fatal in a tropical biosphere festering with insects, parasites, and bacteria. Roosevelt’s carriage injury from 1902 rendered his left leg particularly vulnerable, and the party’s doctor feared that his dominant leg being incapacitated would practically be a death sentence.

On March 28, Roosevelt’s condition had deteriorated with the worsening of his infected right leg. Furthermore, the expedition hit a major obstacle after reaching a large gorge with six waterfalls that would be impossible to get through via their fragile canoes. The only way down was through direct infiltration of the thick jungle, and Roosevelt did not want to be a burden for the other men. He was fully prepared to die, having brought with him a lethal dose of morphine which could provide a quick and easy end. He informed Kermit and Cherrie, “I will stop here.”

Betrayal

Remembering why he had joined the expedition in the first place, Kermit outright refused his father’s orders and vowed that he would protect his life. Roosevelt realized that his own stubborn determination was beaten and, for the first time, acknowledged that his physical well-being was no longer in his hands. Despite believing that he had reached the end, at the eleventh hour he chose to live and trusted Kermit with his life.

As for how they would proceed, Kermit believed that the canoes could be lowered down the falls with ropes, while the men would scale down the cliffs with a reduced baggage load. This was the fourth time they had cut their supplies, but taking everything with them would have been impossible. The plan, however, proved to only be partially successful. There were only five canoes left, while the rest of the cargo had to be moved via a newly-carved trail as the cliffs were too steep to descend. The whole process to exit the canyon took four days, but even upon returning to the river, the party still had intense rapids and more cliff descents to deal with.

Despite his poor health, Roosevelt did his best to keep the men’s spirits up, and he even began gifting the camaradas chocolate bars as a token of gratitude. He also gave them part of his rations, believing that it was the only way he could help amid his incapacitated state. While the vast majority of the workers were good men who loyally performed their tasks, one was not. On April 3, a camarada named Julio had been caught stealing rations from the camp’s supplies, much to the anger of Paishon, the man Rondon had put in charge. Julio fled from the scene and stole a rifle, only to shoot Paishon dead as he attempted to make his escape.

The party now had to apprehend a murderer, but Julio could not get far given the inhospitable conditions of the jungle. Even the pacifist Rondon was incandescent with rage at seeing the unprecedented event of one of his men killing a fellow soldier. Despite this, he still advocated for apprehending Julio alive to face justice in Brazil’s courts. Roosevelt, however, believed that it would be more pragmatic to kill the man outright since keeping him with the group posed risks to their safety. They later found the rifle that Julio stole, which meant that he was hiding somewhere unarmed.

After giving Paishon a burial, the men stayed on guard as night fell to ensure that Julio did not return to the camp and attempt to steal another firearm. The excitement had worsened Roosevelt’s health and Kermit too was suffering from malaria. But having gotten used to the disease, he ignored his health for the sake of taking care of his father. The entire group feared that Roosevelt would die any day, but his fever finally broke by the time they returned to the river on April 6. Incredibly, they also passed by Julio who begged to be taken back, but Rondon insisted on making camp up ahead first.

Roosevelt and Rondon intensely debated what should be done next. The Americans were dismayed that the Brazilian colonel intended on spending the entirety of the next day organizing a search party to apprehend Julio, with T.R. still arguing that they should keep going. Ultimately, they found no trace of Julio and his fate remains unknown to this day. One theory is that he attempted to make contact with an indigenous tribe in a last-ditch effort for survival, but was probably killed by a hostile group like the Cinta Larga. But with no food or supplies, he would have still succumbed to the jungle and died of disease or starvation.

Rubber Men

Apart from Rondon, the rest of the 19-men crew were suffering from malnourishment, disease, or both by the time they moved on from Julio. Yet the end was thankfully near.

On April 11, two men searched for Kermit’s dog which had leapt out of his canoe the previous day. George Cherrie expressed frustration in his journal that the entire expedition had been delayed for what he viewed to be such a trivial matter, but by the time the men returned in the evening with the animal, they also came with good news. They had discovered a vine which had been “cut off with a knife or an ax,” signifying that seringueiros, or rubber-tappers were in the area.

Rubber was previously one of Brazil’s most prized exports, but the industry had long dried up by 1913. Seringueiros were impoverished settlers who lived near rubber trees, and they constantly risking their lives by venturing deeper in the jungle to seek out untapped sources. It was often a brutal, thankless job, and the death rate among workers was exceptionally high. They frequently encountered Indian tribes who saw them as hostile invaders, leading to casualties on both sides. The seringueiros were the link between Brazil’s indigenous world and the civilized world, but few would ever want to be in their position.

The men soon reached a small house which belonged to a seringueiro who was willing to help the group as soon as Rondon explained their position. Roosevelt was battling infection and could hardly even sit up. If he did not receive medical attention soon, he would assuredly die from his injured leg. The former U.S. president was thousands of miles away from home in one of the most remote parts of the entire world, but in some ironic sense, it would also have been a fitting end for the Rough Rider who had always longed to die in glory having achieved something great for his country.

While the other seringueiros who lived nearby were initially suspicious that the emaciated men were possibly hostile Indians (they had not seen anyone from civilization in years), they offered them hospitality as soon as they learned the truth. The men escaping the jungle had been no accident. Only the Cinta Larga decided who would be able to pass through their territory alive, and the fact that the expedition had reached the rubber men’s houses meant that the tribe collectively chose not to engage with them.

The goal of expedition was to meet with Lieutenant Antonio Pyrineus at the confluence between the River of Doubt and the Aripuanã River. The seringueiros informed Rondon’s party that it would take another 15 days to reach this location, which meant that Roosevelt would have to hold on for over a fortnight despite being in the worst condition of the entire group. He relented and agreed to surgery on April 16 which would hopefully improve the condition of his leg without needing to amputate. Anesthetic was naturally not available, but Roosevelt went through the procedure regardless.

This worked in a pinch, but infection was still rapidly spreading throughout T.R.’s body and a real medical facility was needed for him to pull through. While this portion of the river was much easier to navigate than before, most men half of Roosevelt’s age would’ve long expired under the same conditions. But against all odd, the Lion did not die. He held on until April 26 when the party met up with Lieutenant Pyrineus and the two flags of both Brazil and the United States flew proudly in the breeze.

A Hero’s Welcome

Theodore Roosevelt returned to New York on May 19, 1914. He had greatly recovered from his near-death experience in Brazil, but reporters immediately noticed that the former president looked gaunt, thin, and walked with a cane. By the time he had reached the Aripuanã three weeks previously, he had lost 55 pounds since the start of the journey. The expedition had lasted from December 1913 to April of the following year and three people out of the 22 who made the trek down the River of Doubt, now christened the Roosevelt River, had died in the attempt.

While recovering on the trip back to the United States, Roosevelt gained back 25 pounds, but he was a forever changed man after all he had experienced. The press initially hailed T.R. as a national hero and wrote glowingly of his return from the unknown, but it was precisely because his story was so incredible that many in the geographical and scientific community expressed their skepticism.

South America expert Sir Clements Markham and famed explorer Henry Savage Landor publicly slammed Roosevelt as a charlatan and accused him of fabricating his claims. Others defended T.R., but the man himself intended to refute all of his critics when he spoke before the National Geographic Society on May 26. Speaking at Washington D.C.’s now-nonexistent Convention Hall, the crowd of five thousand guests were rapturous in their applause of Roosevelt before he had even uttered a single word. Amid the sweltering heat, diplomats, Supreme Court justices, and members of the Woodrow Wilson administration were all present in tense anticipation.

Roosevelt was visibly weak from the expedition, but his passion for stating the truth of what had happened was unwavering. While his voice was barely audible, journalists took careful notes as he explained in precise detail how the expedition had navigated the River of Doubt. He impressed his American audience with his recounting of the survey, and he did the same the following month when he addressed the Royal Geographical Society in London. It was a packed auditorium incredibly eager to hear Roosevelt’s stories, and he once again humiliated his skeptics.

After returning to the United States, Roosevelt repeatedly praised Colonel Cândido Rondon as being among the bravest men he had ever known, while also crediting his hardworking crew of camaradas that had seen the expedition to the very end for its success. While Roosevelt’s progressivism was not on the same level of Rondon’s, the Brazilian adventure had assuredly changed how he viewed non-white races and indigenous people. But for as much as T.R. wished to play an active role in the rapidly changing events of the 20th century, time moved passed him.

World War I broke out on July 28, 1914, just one month after Roosevelt concluded his European speaking tour. Back in the United States, the Progressive Party folded in 1916, leaving T.R. with little political backing. When the U.S. finally entered the war in 1917, he had hoped to personally lead his own regiment into battle, but President Wilson saw to it that this would never happen. Both men notoriously disliked each other, but rivalries aside, Roosevelt was 59 and hardly in any condition for military service.

T.R.’s health never fully recovered after Brazil, leaving him to spend his final years in a far less active state that he would have hoped for. Just as tragedy marked his early life, Roosevelt too would experience grief toward the end. He was proud of his four sons for enlisting in the Great War at his insistence, but was wracked with guilt after his youngest, Quentin, died on the battlefield at the age of 20 on July 14, 1918. After a continued battle with ailments that were caused either directly or indirectly by what he experienced in Brazil, Theodore Roosevelt himself died in his sleep on January 5, 1919. He was 60 years old.

Fading Into History

The other major players of the River of Doubt expedition, however, lived for quite some time after. Father John Augustine Zahm followed Roosevelt in 1921, passing away at age 70. Although Roosevelt had done his best to preserve his friend’s reputation, Zahm died in relative obscurity and remains a largely forgotten figure today. George Cherrie, however, continued his work in South America and maintained a good reputation among his colleagues. He enjoyed spending time with his family after retiring from the field and lived to be 82, passing away on January 20, 1948.

Unfortunately, glory did not follow Kermit Roosevelt. Like many sons of great men, he constantly lived in his father’s shadow and felt intense pressure to live up to expectations that were likely impossible to meet. While he married Belle Willard soon after returning from Brazil in 1914, the death of his father just five years later was a bitter blow. Kermit’s problems with alcoholism only worsened as time went on, his numerous extramarital affairs brought shame to his family’s name, and he squandered his wife’s inheritance due to poor investments during the Great Depression. When WWII broke out, Belle asked her cousin President Franklin Delano Roosevelt to provide Kermit for a position in the military.

What could have been Kermit’s chance to turn his life around and return home a war hero instead proved to be his end. While he initially served in Norway and North Africa with distinction, his alcoholism contributed to chronic health problems that made him unfit for combat. His final posting was at Fort Richardson in Alaska where he was to assist Eskimos and Aleuts in campaigns against the Japanese, but he died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound on June 4, 1943. He was 53 years old, having not even lived to be older than his father. Kermit’s brothers, Archibald Roosevelt and Theodore Roosevelt Jr., also served in WWII, with the latter famously dying shortly after D-Day in 1944.

Incredibly, it was Colonel Cândido Rondon who lived the longest out of everyone who participated in the River of Doubt expedition despite having come from the most harrowing childhood conditions. Owing to his vigorous exercise routine and healthy lifestyle choices, Rondon reached the age of 92, passing away on January 19, 1958 after many more decades of work with Brazil’s indigenous populations. While the network of telegraph poles he established quickly became obsolete with the advent of radio, Rondon, like Roosevelt, was hailed as a national hero in his country.

Rondon, while less discussed in Brazil today compared to other figures who shaped the nation’s history, is still remembered as a man ahead of his time. The colonel’s expeditions into the jungle would signify the end of many indigenous tribes’ isolation and lead to their declining numbers, but this was an inevitable reality of the early 20th century across many countries. Rondon knew that nothing could stop this, which is why he strove to integrate them into modern society.

Owing to his achievements, the Brazilian government in 1956 named the state of Rondônia after him. This massive honor marked just how far he had come from being a poor orphaned boy born into one of the most impoverished places in South America to becoming a mover of history.

Legacy of Doubt

The Roosevelt-Rondon Scientific Expedition, while crucial in contributing to understanding of the region, was only the start. After others made failed attempts, George Miller Dyott returned to South America in 1927 and lead the next successful expedition through the River of Doubt. He confirmed what Roosevelt had originally reported, but no one remembers the second person who climbed Mount Everest. A third expedition conducted decades later in 1992 with modern technology was more of a reenactment than anything groundbreaking, but it was officially sponsored by the Theodore Roosevelt Association and even featured the participation of Roosevelt’s great-grandson.

Today, Theodore Roosevelt’s River of Doubt expedition is less remembered compared to his other achievements. Most biographical texts often dedicate little more than a few paragraphs to the event despite it being a major factor in Roosevelt’s eventual death. It wouldn’t be until 2005 when American journalist Candice Milllard wrote The River of Doubt, which remains the definitive text on the subject and provided much of the material featured in this article. For those who wish to learn more, it comes highly recommended.

In 2021, HBO released a four-episode television miniseries which adapted the events of the expedition with surprising historical accuracy. It appears to have been largely based on Millard’s book, down to dialogue being lifted from the page word-for-word. While a Brazilian production, the writers clearly did their research on American history and Roosevelt’s life, as the journey is regularly interspersed with flashbacks from his political career.

Naturally, some things were changed for the sake of dramatization and viewer convenience. Rondon is shown speaking to Roosevelt and the Americans in fluent English, when the real Rondon had to rely on interpreters. Kermit appears to feel more outwardly guilty for the death of Simplicio and even requests that the other camaradas whip him as punishment, but there is no record of this happening. Roosevelt’s relationship with William Howard Taft is also explored in greater detail via the flashbacks. Taft is depicted as having attended Roosevelt’s 1914 speech in Washington D.C. and cheering him on after mending their strained friendship, but this is pure fiction invented for the series.

When it comes to the overall production, however, The American Guest is top-notch. All the actors look like they were born to play their respective parts, with Aidan Quinn and Chico Diaz showing an uncanny resemblance to the real Roosevelt and Rondon. Dramatic devices aside, I was amazed at how much this series strove to capture all the major details of the expedition. History buffs who are intimately familiar with Roosevelt’s life are likely to be pleased. Martin Scorsese and Leonardo DiCaprio are apparently working on a Theodore Roosevelt biopic, but with the increasing likelihood of that film possibly not being made, I’m glad that this show at least exists.

Given its importance to Roosevelt’s life and to U.S.-Brazilian relations, one may wonder why the River of Doubt expedition is generallly forgotten by the public in both countries. One reason is likely because Roosevelt’s return to the United States coincided shortly before the outbreak of WWI, which caused the public to quickly become concerned with more pressing events. Roosevelt died only a few years later, and much of the discourse around him quickly became focused on the legacy of his military and political career.

It’s a testament to everything Theodore Roosevelt ever accomplished that something so incredible as him contributing to the navigation of an unknown river in a hostile jungle is considered to be one of his lesser-known achievements. While the Lion may have been able to live for a few years longer had he not gone, he certainly would have rebuffed the notion of missing the chance to cap off a lifetime of adventure.

If one goes to the Rio Roosevelt today, they will experience some of the finest natural landscapes offered by the Amazon rainforest. It’s a remote site that can only be accessed via air, but its beauty has not faded since it was surveyed over a century ago. Theodore Roosevelt and Cândido Rondon would surely be pleased had they known that it would remain preserved for future generations to admire.

A Message from Foreign Perspectives

Dear Reader,

If you’ve made it this far, let me thank you from the bottom of my heart for taking the time to read my work! At Foreign Perspectives, I cover a variety of topics related to my own personal interests from life in Japan to film analysis, but one of my goals is to also shed light on lesser-known historical events and individuals.

This piece you just read is one the longest and most detailed I have ever written. Normally such articles which take more time to produce are reserved only for paid subscribers of my Substack, but I’ve chosen to make this one free for all. There are two reasons for this.

First, I wanted to bring more attention to Theodore Roosevelt’s expedition in Brazil. After reading Candice Milllard’s book on the subject, I was surprised to discover that there is relatively little coverage of it online and most articles about it don’t go into much detail. If you liked what you read here, I highly recommend Millard’s work for the definitive account of the River of Doubt expedition because she goes into far more detail than I ever could in this one piece (which is already approaching novella-length already!). I hope that the Google search engine optimization gods will smile upon me and make my piece one of the first results when people look up this subject.

The second reason is to provide free subscribers or those who are not yet subscribed at all a full sample of what they would be getting if they opted for a paid subscription to Foreign Perspectives. Most of my pieces do not get this long, but I’ve generally paywalled articles that involve more research and planning, as well as ones that tend to be more about specialized topics. There will always be free articles, but I’m hoping to transition into more paid content to keep this enterprise sustainable.

I’m very thankful for the dozens of readers who have already opted for paid subscriptions because my Substack provides me with a needed source of supplemental income next to my freelance work for other websites. My writing has reached so many people this year and Foreign Perspectives considers to see considerable readership growth each month.

If you appreciate long-form articles like these and the work I do, please consider a paid subscription to get full access to everything Foreign Perspectives has to offer. Your patronage is a vital part of this Substack, and I hope to continue producing high-quality content.

Thanks again to all who have subscribed!

Best regards,

Oliver Jia